Summary

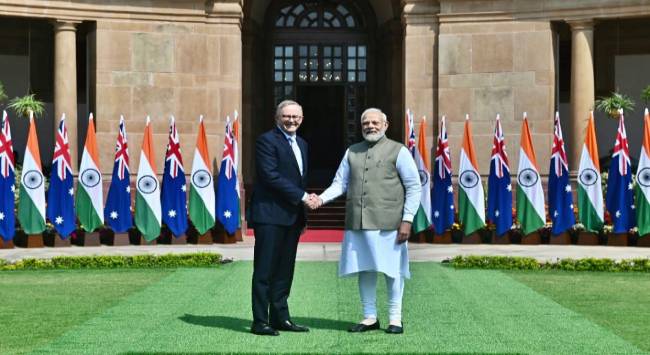

The four-day visit of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to India in March 2023 has helped consolidate Australia’s position in the A-list of India’s strategic partners. Thanks to the continuous political efforts in both capitals in recent years, the long-standing synergies between the two nations are now being translated into concrete outcomes in the political, economic and security domains.

Few of Delhi’s relations have advanced as rapidly in the last few years as those with Canberra. The same can be said of India’s place in Australia’s international relations. Few Asian observers would have bet a decade ago that the relationship between India and Australia, which ranged from irritable to indifferent in the second half of the 20th century, would become a valued strategic partnership for both in the 21st century.

Although the two sides shared democratic traditions, the English language, extended neighbourhood and massive economic synergies, it was hard to bring them close together. Mutual political neglect, ignorance of commercial possibilities, and the contested Cold War geopolitics limited the possibilities for bilateral relations during the 20th century.

The Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Australia in 2014 was the first Indian prime ministerial visit in nearly three decades. Rajiv Gandhi went to Australia in 1986. The long gap between the two visits underlined how profoundly India had underestimated the importance of Australia for India’s economic and security interests. Recent years have certainly seen the end of this political neglect. Sustained high-level exchanges have provided much-needed political momentum to the India-Australia partnership. Australia has long taken the initiative to expand its engagement with India. After much hesitation, Delhi is now reciprocating. In 2022, 10 union ministers from India travelled to Australia.

During the Cold War, the occasional efforts at overcoming the political divergences in the worldviews of Delhi and Canberra did not succeed because there was little economic cooperation between the two countries. Only after India’s economic liberalisation that followed soon after the Cold War ended did the complementarity between India’s economic growth and Australia’s rich natural resources come into view. However, policies took nearly three decades to catch up with new possibilities. The Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA) that opened the door for freer commerce between the two nations came into force at the end of 2022.

One of the main objectives of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s visit to India was to go beyond the ECTA and move towards a full-fledged free trade agreement between the two countries. During his joint press conference with Modi, Albanese expressed hope for the conclusion of the Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (CECA) talks before the end of 2023. Although Modi did not publicly endorse the goal, he has ordered the Indian bureaucracy to make haste. Soon after Albanese concluded his visit, the Indian commerce minister Piyush Goyal and the Australian trade minister met to accelerate the talks on the CECA. While there are many issues to be sorted out, there is a recognition by both sides that the current trade volumes of about US$31 billion (S$ 41.8 billion) must be pushed up to US$100 billion (S$134.9 billion) by the end of this decade.

An important element of the bilateral partnership is the education sector. Nearly 60,000 Indian students are now in Australia. During his visit to Gujarat, Albanese announced the launch of the Deakin University campus at the GIFT city outside the capital, Gandhinagar. The two sides signed an agreement on mutual recognition of educational degrees. This should facilitate dual degrees and deeper collaboration between the higher educational institutions of the two countries. Meanwhile, the deterioration of the regional security environment, marked by the rise of an increasingly assertive China that seeks to reorder the region to suit its interests, has nudged Delhi and Canberra closer together in deepening their bilateral security cooperation. Further, India and Australia are joining hands in minilateral institutions, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and regional multilateral forums such as the Indian Ocean Rim Association and the East Asia Summit.

Nevertheless, Delhi and Canberra understand that China is here to stay as a major force in Asia and that India and Australia have no option but to engage it. Despite the gravity of the conflict on the border, Delhi has sustained a military dialogue with Beijing to resolve the border tensions. In Australia, Albanese has toned down the anti-China rhetoric of his predecessor, Scott Morrison, and signalled a commitment to engage and cooperate with China where possible. Delhi and Canberra are eager to develop a reasonable and mutually beneficial relationship with Beijing. Neither wants to join a containment ring against China but is determined to promote a stable regional security architecture in the Indo-Pacific. Both are expanding security ties with the US and Japan and are unwilling to be cowed down by Beijing’s pressure tactics.

The convergences on the economic and security front have been reinforced by the rapidly growing Indian diaspora in Australia. At nearly a million, the Indian-origin population in Australia is now about three per cent of the total 25 million people inhabiting the nation. The flows of Indian technical talent and skilled labour into Australia will likely grow further in the years ahead. However, this ‘living bridge’ also generates new problems. Modi publicly flagged the recent vandalisation of Indian temples in Australia by Khalistani groups with Albanese. The Australian prime minister has underlined Canberra’s commitment to crack down on hate crimes. As the Indian communities go abroad, it is natural that their internal conflicts get carried over into other societies. Preventing these conflicts from overwhelming the relationship should be an important political objective for Delhi and Canberra.

. . . . .

Professor C Raja Mohan is a Visiting Research Professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute in the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at crmohan@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: MEAIndia Twitter Account

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF