Summary

In light of the deteriorating military-political situation in Afghanistan, there are potential threats of instability and mass crossing-over of refugees to the Central Asian republics that share borders with Afghanistan. Russia, the primary security provider in the post-Soviet space, is now facing the gargantuan task of maintaining security and averting a potential refugee crisis in the region.

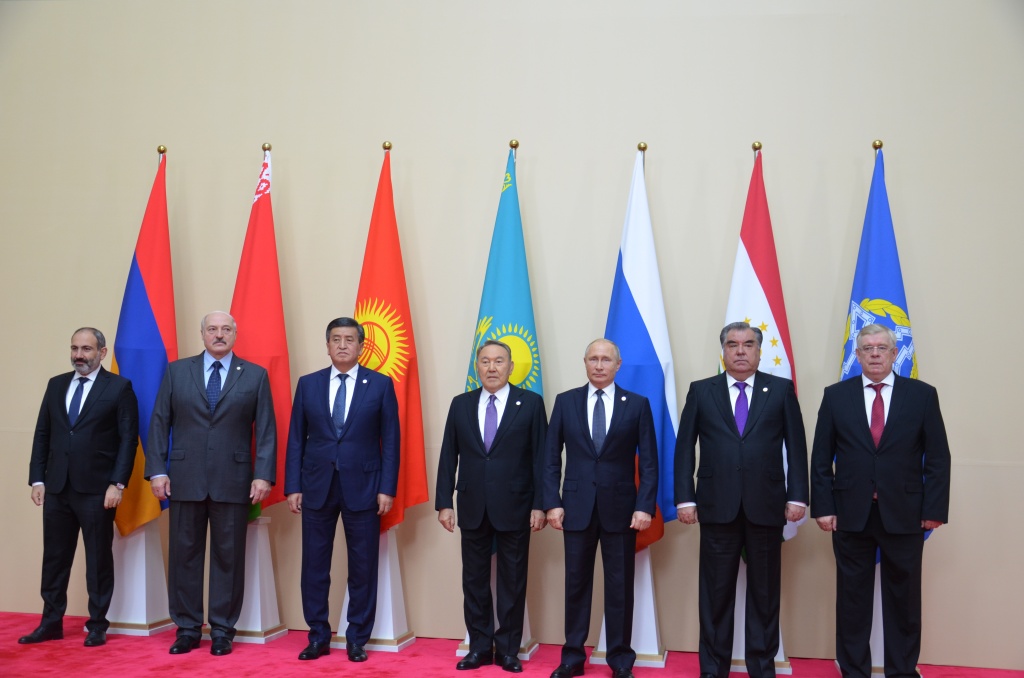

On 23 August 2021, the Russian-led security bloc, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), held emergency talks on Afghanistan and the members agreed to coordinate joint action to counteract the threats from Afghanistan and combat illegal migration. On the same day, Russian President Vladimir Putin cautioned against the movement of “militants under the guise of refugees” into several former Soviet republics that share a border with both Russia and Afghanistan. The Taliban takeover of Kabul has impacted regional security with many Afghan citizens rushing to leave for neighbouring countries. Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, the three Central Asian Republics (CARs) that share a border with Afghanistan, have increased security and manpower in fear of the fighting and potential refugee influx. Hundreds of Afghan refugees have reportedly crossed into Uzbekistan via bridge, river and flight.

In early July 2021, Tajikistan requested assistance from the CSTO to handle security along the Afghan-Tajik border when Afghan government forces fled into Tajik territory. While it was assessed that the situation did not require CSTO involvement, Russia is reportedly providing funds for Tajikistan to construct a new border outpost. In early August 2021, a Taliban delegation in Moscow announced that it controlled 85 per cent of Afghan territories and provided reassurance to Russia that it would not allow Afghanistan to be used as a platform to attack neighbouring countries. Correspondingly, Russia started joint military drills along the Afghan border with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in anticipation of violence emanating from Afghanistan.

While there is no direct military threat against Moscow from Kabul, with the Taliban takeover and impending security vacuum post-withdrawal of American forces, Afghanistan could become a volatile site for terrorism and drug trafficking. Additionally, Moscow fears that the growing strength of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in the region would spread radical Islamic sentiments in Muslim-majority CARs. In the Russian eyes, the Taliban are a lesser evil compared to ISIS. The potential spillover of Afghan instability, extremism, and violence into Central Asia pose huge security concerns for Moscow. Now, aiding the CARs in securing their borders and avoiding a refugee crisis is of paramount importance to Russia.

The last 20 years of American-led military operation in Afghanistan has largely shielded the CARs from pertinent threats and instability by containing the Taliban forces within Afghan borders. With American departure, the Russian role and influence in the region would most likely be enhanced. Moscow has voiced opposition towards the redeployment of American forces in Central Asia. Thus, moving forward, the responsibility of security in the region would lie mainly with the regional powers – Russia and China. There will likely be new security agreements and deepening of regional cooperation efforts centring on Afghanistan amongst Russia and the CARs, either through bilateral channels or the CSTO.

The CSTO is viewed primarily as a platform to coordinate military exercises and discuss security situations among former Soviet Republics in Eurasia. Further, as Beijing-Moscow recently affirmed the mutual willingness towards working together to build an inclusive government in Kabul, it is expected that they would work together through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to coordinate security efforts among the regional powers. The latest statement by the SCO Secretariat reaffirmed the member nations’ commitment to aid Afghanistan in building a stable future.

Notably, the CSTO and the SCO do not include any Western powers. It is representative of a non-Western regionalism among the Asian powers that codified the dominance of Russia and China. While some analysts have criticised the inefficacy of the CSTO and SCO, both organisations serve the important function of “protective integration” for Eurasian powers to cooperate with one another without being subjected to intrusion of external values and impingement of sovereignty.

Having stepped up its diplomatic activity regarding Afghanistan by establishing communication with the Taliban in 2015, Russia has also collaborated with many countries like the CARs, the United States, Pakistan, Iran and China on multiple occasions to discuss Afghanistan. With its help, the regional countries could come together to develop a coherent strategy to contain security risks from Afghanistan.

That being said, Russia has yet to decide on its stance towards the Taliban and the relationship it wishes to build. While Moscow expresses the openness to engage with a Taliban-led government, it has not considered the development of military ties with the Taliban. The group is still regarded as a “prohibited movement” in Russia and Dmitriy Shugaev, Director of Russia’s Federal Service of Military and Technical Cooperation, declared that Russia “will not have military affiliations with such a group”.

Given the ongoing uncertainty in Afghanistan, Russia faces a tough challenge to develop a flexible strategy that prioritises security and controlled movement of people along the borders. Establishing good relations with the Taliban might help but Russia will first need to ascertain its recognition of the group and the role it hopes to play in Afghanistan.

. . . . .

Ms Claudia Chia is a Research Analyst at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at claudiachia@nus.edu.sg. Mr Zheng Haiqi is a PhD Candidate in the School of International Studies, Renmin University, China, and a Visiting Scholar at ISAS. He can be contacted at zheng.haiqi@nus.edu.sg.. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: CSTO website

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF