Summary

Political compulsions have compelled the Indian central government to rethink the New Pension Scheme which was adopted in 2004. With the intent of creating a corpus fund to meet the pension liabilities, a defined contribution pension scheme, as against the earlier defined benefit scheme, was set up by the Indian government. However, this scheme ran into rough weather on grounds of leaving pensioners at the mercy of market vagaries. The government has now announced a new Unified Pension Scheme which combines an assured element too.

The Indian government’s decision to switch its pension plan from a defined benefit to a defined contribution has been meeting with headwinds. The mechanics of the scheme, introduced in 2004, comes in to the limelight with the onset of every election within the country. Considering the culture of ‘freebies’, which has been pervading the electoral scenario, political parties have made every attempt to woo the voter with grandiose promises. The most recent such ‘freebie’ attraction has been the promise to switch back to the defined benefit scheme, which assures all retirees a monthly pension which is half of the last pay drawn. The central government has not fallen prey to the temptation to announce a rollback of the defined contribution scheme. However, considering the switch to the old scheme in states such as Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Punjab, the central government has had to rethink its own strategy. It has now announced a new Unified Pension Scheme (UPS) which seems to be a major political signal before the election to the Jammu and Kashmir, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Maharashtra assemblies.

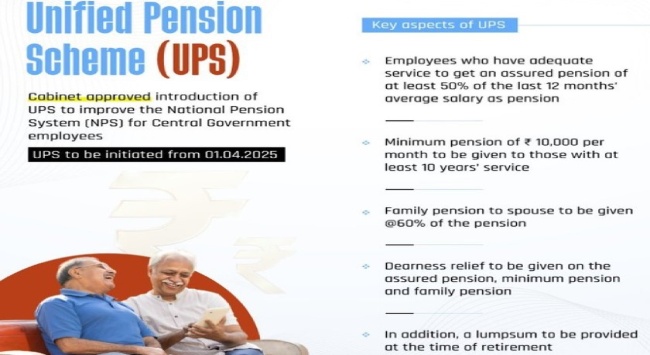

The salient features of the UPS, which is scheduled to be introduced in April 2025, are:

- An assured pension of 50 per cent of the average basic pay drawn over the last 12 months prior to superannuation for a minimum qualifying service of 25 years. This pay is to be proportionate for a lesser service period up to a minimum of 10 years of service.

- Assured family pension at 60 per cent of the pension of the employee immediately before her/his demise.

- Assured minimum pension: at ₹10,000 (S$165) per month on superannuation after a minimum of 10 years of service.

- Inflation indexation on assured pension, assured family pension and assured minimum pension. Dearness relief will be admissible based on the All India Consumer Price Index for Industrial Workers as in the case of service employees.

- Lump sum payment at superannuation in addition to gratuity at one-tenth of monthly emoluments (pay + DA) as on the date of superannuation for every completed six months of service. This payment will not reduce the quantum of assured pension.

Most significantly, the UPS offers an assured pension of 50 per cent of the average salary of the last 12 months subject to a minimum of ₹10,000 (S$165).

The National Pension System was introduced in 2004 by the then National Democratic Alliance government, since the Old Pension Scheme (OPS) was unfunded, in that there was no corpus created from which the pay-out could be done. As a consequence, the government’s financial liability was likely to balloon to unsustainable levels.

The fact that the OPS would have led to huge liabilities is borne out by data. In 1990-91, the centre’s pension bill was ₹2,997.5 million (S$54.5 million) and that of all states put together was ₹2,871 million (S$52.2 million). By 2020-21, the centre’s pensions bill had jumped 58 times to ₹174.9 billion (S$3.18 billion), and for the states, it had shot up 125 times to ₹354.75 billion (S$6.45 billion).

The National Pension System dispensed with the assured pension concept and introduced the concept of the employee funding his pension with a contribution of 10 per cent of pay and dearness allowance, with the government contributing 14 per cent. Under the New Pension Scheme (NPS), this contribution was increased to 18 per cent. The retirees, under the NPS, could choose from a range of schemes from low risk to high risk through pension fund managers promoted by public sector banks/financial institutions, and private companies. The drawback of the NPS was that it gave lower assured returns, and required the employee to contribute, unlike the OPS. This became the red rag for employees and political parties.

In light of the adverse reaction that the NPS was drawing and the fact that promises of the political parties to revert to the old scheme were drawing voters, the central government constituted a committee under the leadership of the Finance Secretary in 2023 to review the NPS. This committee has brought forth the proposal which has been approved by the government. The new scheme does not leave the beneficiary to be entirely at the mercy of the vagaries of market forces and it will apply to all the retirees who were covered under the NPS. Their pension will be recalculated as per the UPS and they will be eligible to arrears after adjustment for what has been paid to them. The government, however, provides an alternative for retirees to continue with the NPS in case they so desire. However, calculations done by certain agencies indicate that on average, a pensioner will receive an increase of about 19 per cent for those joining on a monthly salary of ₹50,000 (S$825) and may see an annual increase of about three per cent.

The UPS applies to central government employees. It can be adopted by state governments if they choose to do so.

In announcing the new scheme, the government has not backtracked on its core principle of a defined contribution mechanism. It has merely limited that principle to 50 per cent of the pension admissible and provided top-ups which will limit government liability towards the pension. It, however, deviates from that principle in assuring a minimum pension of ₹10,000 (S$165) to those who have served for 10 years. The scheme also has the added benefit of being based on actuarial calculations to assess the liability accruing to the government in bridging the gap. To that extent, it may be considered win-win for both sides. However, from the macro-economic viewpoint, it is a step back from a major reform introduced after much deliberation and negotiation with all stakeholders and is likely to impose substantial costs on the economy.

. . . . .

Mr Vinod Rai is a Distinguished Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute in the National University of Singapore (NUS). He is a former Comptroller and Auditor General of India. He can be contacted at isasvr@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Pic Credit: https://upspensionscheme.com/my-gov-ups-united-pension-scheme-cabinet-devisions-hindi-posters/

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF