Student Mobility in the Asia-Pacific and South Asia: Trends and Impact of COVID-19

Amitendu Palit, Divya Murali, Mekhla Jha

7 September 2021Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected cross-border movement of people. Apart from international travel for leisure and business, the pandemic has greatly impacted the international mobility of students. These include students from South Asia travelling to other countries for higher studies. This paper studies the movement of students within the Asia-Pacific region to determine the cross-regional patterns of movements among sub-regions of the Asia-Pacific. Using empirical measures (student mobility ratio, student immigration preference index and student emigrating preference index) based on student movement data obtained from the United Nations, the paper identifies the prominent higher education service exporters and importers in the region. It also identifies the preferences of both inbound and outbound students on their choice of higher education destinations.

The insights obtained from the empirical analysis identify South Asia as the Asia-Pacific’s most prominent higher education service importer. Large outbound students from India and Nepal contribute to the region’s imports. These students have also been responsible for enriching the Oceania region’s prospects as an education service hub and exporter. The paper argues that strong COVID-19 travel restrictions maintained by the Oceania region and lack of certainty over their removals might impact preferences of outbound students from South Asia as they look closely at the West for higher study options.

Overall Student Mobility in the Asia-Pacific and Its Sub-regions

Student movements are a major indicator of trade in educational services. When students travel abroad to study, paying tuition and other fees to a higher education institute in a foreign country, it is considered an export of education services under mode 2 of services trade categories as defined by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and World Trade Organization.[1] Countries with student mobility ratios[2] greater than 1 are net exporters of education services. These are countries whose education institutions attract foreign students with the latter paying to study in the former. On the other hand, countries with student mobility ratios less than one are those that are net importers of education services. These are countries from where students move out to foreign countries in larger proportions than foreign students coming in.[3]

This paper computes student mobility ratios for countries and regions in the Asia-Pacific to identify the patterns of student movements. The paper uses data from the ‘Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students’ database of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).[4] The data reports student movements before the outbreak of COVID-19 and provides information on the overseas destinations that students choose for higher studies and the countries they belong to. The countries from the Asia-Pacific that are included in the database are in Appendix 1.

Student mobility ratios for the Asia-Pacific are reflected in Table 1. The ratio could not be calculated for Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Cambodia, the Philippines and Thailand due to non-availability of inbound student data in the UNESCO database.

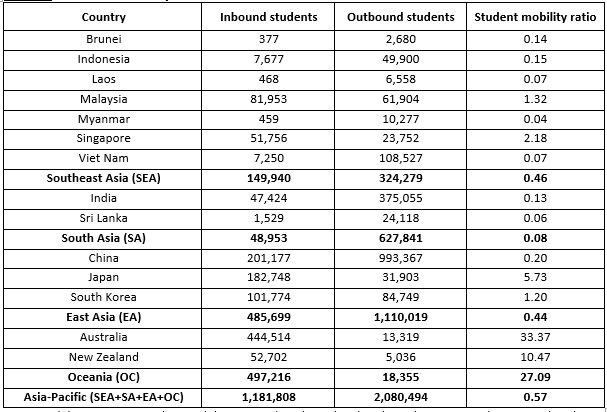

Table 1: Student mobility ratio for the Asia-Pacific

Note: While computing student mobility ratios, the inbound and outbound movements have considered movements not just within the Asia-Pacific, but for the rest of the world also.

Source: http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow. Computations by the authors.

The following insights emerge from Table 1:

- The Asia-Pacific region, as a whole, has more students going out to study elsewhere than students coming to study in the region. Most of the sub-regions within the Asia-Pacific – Southeast Asia, South Asia, and East Asia – have student mobility ratios that are less than one (Table 1). The low ratios for these regions influence the overall ratio for the Asia-Pacific, notwithstanding a very high student mobility ratio for the Oceania sub-region.

- Except for Oceania, which is a prominent exporter of education services given a large number of its inbound students, other sub-regions of the Asia-Pacific are net importers of education services. Among these sub-regions, South Asia has the least number of inbound students, compared with its outbound students, making it the largest importer of education services in the Asia-Pacific.

- Neither India nor Sri Lanka – the two South Asian countries in the analysis for whom student mobility ratios could be computed – have these ratios greater than 1. This is in contrast to Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia and Singapore, East Asian countries like Japan and South Korea, and the Oceania countries of Australia and New Zealand, all of which have student mobility ratios of more than one (Table 1). India and Sri Lanka, thus, are importers of educational services with far more students from these countries moving out to study abroad, compared with inbound students choosing to study in them. On the other hand, despite Southeast Asia and East Asia being regions with net importers of education services, Malaysia and Singapore from the former, and Japan and South Korea from the latter, are net exporters.

- India is the second-largest country in the Asia-Pacific, after China, in numbers of outbound students (Table 1). India and China account for 18 per cent and 48 per cent respectively of the total outbound students from the region, followed by Vietnam with five per cent. The fact that India (along with China) accounts for nearly 65 per cent of the total outbound students from the Asia-Pacific has significant implications in terms of the impact on the global education market if students from India and China are unable to travel overseas due to restrictions induced by COVID-19.

- The impact of the likely disruptions in outbound student flows from India and China can be significant for Asia-Pacific countries like Australia and New Zealand. The penultimate section of the paper will look at these impacts more closely. Given the very high student mobility ratios these two countries have, it is expected that among the foreign students they receive, Indian and Chinese students would be significant with concomitant disruptive effects.

Student Mobility within the Asia-Pacific

Movements of students from within the region itself contribute a significant part of student movements within the Asia-Pacific. Identifying these movements gives an idea about the extent to which inbound and outbound students for sub-regions and countries of the Asia-Pacific, come from the region itself. These trajectories are captured in Table 2.

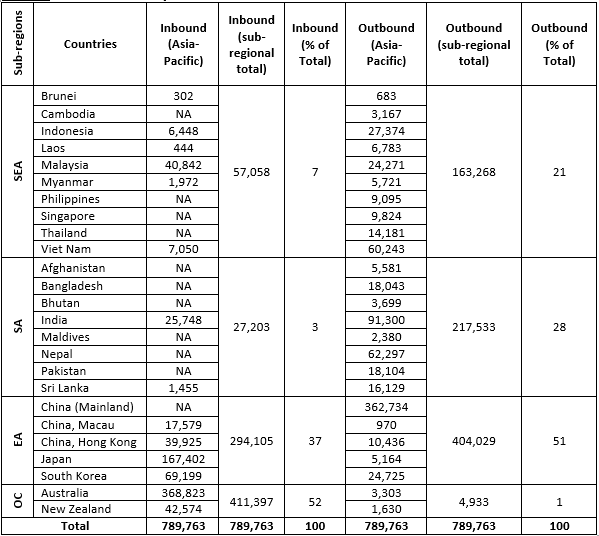

Table 2: Student mobility within the Asia-Pacific

Note: SEA, SA, EA and OC are abbreviations for Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Asia and Oceania respectively. NA: Not available.

Source: http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow. Computations by the authors.

The following insights emerge from Table 2:

- Malaysia, India, Japan and Australia are the top destinations for inbound Asia-Pacific students as far as moving within the region is concerned. The largest number of outbound students heading for higher studies within the Asia-Pacific are from China, India, Nepal, Vietnam, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Students from the major South Asian countries are among the largest flows headed for destinations within the Asia-Pacific. As a region, however, the sheer size of outbound students from mainland China makes East Asia a larger source of outbound students than South Asia. It is, therefore, hardly surprising that East Asia accounts for more than half of the outbound students from the region that are moving within the region.

- Following the earlier identification of the Oceania region as a net exporter of education services, the intra-Asia-Pacific movements throw further light on the roles of Australia and New Zealand. Oceania accounts for 52 per cent of the inbound student traffic from within the Asia-Pacific. Within Oceania, Australia alone accounts for almost 90 per cent of the inbound students. Australia’s prominence as an exporter of educational services has much to do with the students it receives from within the Asia-Pacific region.

- India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka together account for nearly 95 per cent of the outbound student traffic from South Asia headed elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific. There’s no surprise in India accounting for the largest share of these students given its much larger population. However, large populations don’t necessarily imply relatively larger outbound students. This is evident from Nepal being the second-largest source of outbound students from South Asia – higher than those from its other more populous regional neighbours – Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

A closer analysis of major ‘destination’ countries for inbound students, and the major countries they receive the students from, sheds more insights on the specific country-wise pattern of movements. Table 3 identifies the top destination countries for each sub-region of the Asia-Pacific – Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Asia, and Oceania – and lists the top three countries from within the Asia-Pacific that are the largest sources of foreign students for these destinations.

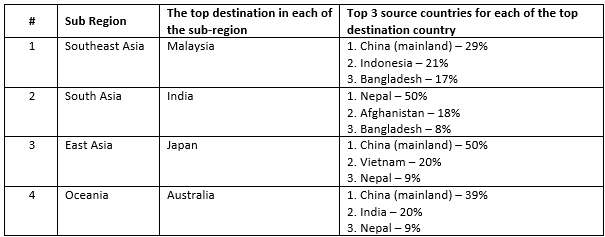

Table 3: Top student destinations for sub-regions in the Asia-Pacific and their major source countries

Source: http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow. Computations by the authors.

For all the top destinations in the four sub-regions of the Asia-Pacific except India, China remains the largest source of inbound students. For India, Nepal constitutes half of the inbound students. Nepal is also among the largest sources of foreign students for Japan and Australia as well. This marks Nepal as a country from South Asia whose dependence on overseas destinations for higher tertiary education is significantly high. Bangladesh is also another country from South Asia from where significant students are moving to Malaysia and India. Finally, India, as noted earlier in the discussion on overall student mobility, is one of the largest sources of foreign students for Australia after China. Thus, Australia’s dependence on students from India and Nepal is significantly high, underpinning the role of students from these countries in Australia’s high educational service exports.

The Asia-Pacific and Regional Mobility Preferences

The ‘preference’ of outbound students in choosing locations is important in deciding which countries distinguish themselves as major education destinations. Concerning the Asia-Pacific region and movement of students within its geography, it is important to have an idea of such preferences. This would help in identifying the roles of the Asia-Pacific countries in enabling the higher education destinations of the region, such as Australia, in achieving and retaining its appeal.

Student preferences are obtained by computing two mobility preference indices. These are the Student Immigration Preference Index (SIPI) and Student Emigration Preference Index (SEPI) respectively.[5] These indices are computed by combining the movements of students from the Asia-Pacific region within itself, as well as to the rest of the world.

The values taken by the SIPI and SEPI indices indicate the mobility preferences of students. Regions and countries with SIPI of more than 0.5 are those with a higher share of inbound students from the Asia-Pacific region as a proportion of their total inbound students. These are, therefore, destinations within the Asia-Pacific that are preferred by outbound students from elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific. Those destinations, for which the SIPI value is less than 0.5, are ones with a lower proportion of Asia-Pacific students in their total inbound students, thereby becoming locations with a lower preference for Asia-Pacific students.

Similarly, a SEPI value of less than 0.5 is indicative of the regions and countries with lower proportions of students heading for the Asia-Pacific in their total outbound students suggesting a lower preference to move to the Asia-Pacific compared to the rest of the world. On the other hand, SEPI value of more than 0.5 outlines a clear tendency for moving within the Asia-Pacific.

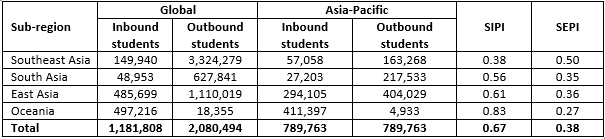

Table 4: Asia-Pacific mobility preference indices: SIPI and SEPI

Source: http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow. Indices developed and computed by the authors.

The following insights emerge from Table 4.

- The Asia-Pacific, as a whole, is a region where its students show a distinct preference for studying within the region. The high SIPI value of 0.67 is contributed largely by the high SIPI of Oceania (0.83), along with East Asia (0.61) and South Asia (0.56). Southeast Asia is the only region within the Asia-Pacific where SIPI is less than 0.5 reflecting a preference of its students to go outside the Asia-Pacific. The fact that inbound students within the Asia-Pacific region are largely contributed by intra-migration (originating and moving within the Asia-Pacific) as opposed to inter-migration (originating from anywhere in the world and moving to the Asia-Pacific) has important implications for student movements within the region that are affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The SEPI value for the Asia-Pacific is 0.38 and it indicates that the majority of outbound students from the region prefer moving out of the region. The low overall SEPI value is consistent with low values for South Asia, East Asia, and Oceania. More of the outbound students from these regions are inclined to move out of the region. Nonetheless, some destinations within the region (for example, Australia and Japan) do attract a large number of regional students too. When looked specifically concerning individual countries with large outbound students, such as China and India, SEPI values indicate that while the larger proportion of the outbound students move out of the region, a considerable section remains within the region. Most of the latter are headed for Australia as revealed by Table 3 earlier.

- South Asia symbolises the two major preferences in student mobility noted for the Asia-Pacific at large. The majority of its inbound students are from the Asia-Pacific. But its outbound students largely move out of the region. To a large extent, student movements connected to India can explain these tendencies. India’s inbound students are largely from the rest of the South Asian region, thereby qualifying them as students from the Asia-Pacific itself. Outbound students from India, however, are more inclined to move out of India. Given the large volume of these students, which is second only to China, despite most of them moving out of the Asia-Pacific, many still head for countries in the Asia-Pacific. These include countries like Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Malaysia and presumably Singapore.[6]

- It is hardly surprising, therefore, that these above countries turn out to be those with higher student mobility ratios (Table 1) and exporters of education services. They are exceptions in an Asia-Pacific that is otherwise a net importer. The largest among these is South Asia. While India does obtain some educational exports due to the inbound students it receives mostly from the neighbourhood, the rest of the South Asian countries are almost entirely education service importers.

COVID-19 and student movements: The South Asian perspective

The COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly disruptive for students. At primary and secondary levels, students have had to transition to online learning. At the tertiary level too, online learning has become the main mode of instruction. From the perspective of students looking to move overseas for education, the restrictions on travel have produced multiple challenges. These challenges range from having to adjust to the new modes of learning and being hindered by available capacities, to overseas education becoming a distant and inaccessible prospect.

South Asia, as revealed by the insights shared in the paper so far, has many outbound students. Its low student mobility ratio (Table 1) underscores the high volume of outbound students, compared with inbound ones. These are led by students from India. Indian students travel outside South Asia to other countries in the Asia-Pacific, most significantly to Australia and New Zealand (Appendix 2). For several months, Indian students have been unable to travel to Australia with current circumstances indicating such passage is unlikely before early 2022.[7] Border restrictions in New Zealand and Singapore have also prevented Indian students from travelling to these countries.[8]

Much as it is disruptive and frustrating for Indian students who are already enrolled in university programmes in various Asia-Pacific destination countries, most of them can continue their studies. This is largely due to access to online learning facilities, enabled by internet connectivity. The problem is far more for students elsewhere in South Asia. Nepal, with a significantly large number of outbound students, many of whom are headed for Australia and New Zealand that are among the top choices of Nepalese students,[9] are probably encountering more difficulties in this regard. Access to digital facilities is not uniform across the South Asian region with such deficiencies being particularly pronounced in a land-locked country like Nepal.

To a very large extent, the prospects of students from India and South Asia are endangered till travel conditions normalise. For smaller South Asian countries like Nepal, Bhutan, the Maldives and Afghanistan, from where several students come to India for higher studies (Appendix 2), the pandemic has obstructed movement making their education prospects bleaker. The resumption of air travel between India and the Maldives, Nepal and Bangladesh should improve the situation for students. However, the possibility of these students, along with those from India for returning to the other education hubs in the Asia-Pacific, appears very remote at this stage.

While it is still too early to reflect, the prospect of South Asian students “substituting” preferences for overseas study locations cannot be overlooked. The longer borders remain closed in the Asia-Pacific and uncertainties prevail over the commencement of onshore campus learning, the stronger would be the incentive for outbound students to search for other options. Australia, for example, is currently the fourth largest destination for Indian students after the United Arab Emirates, Canada, and the US.[10] Canada, which has already over the years become an attractive destination for Indian students due to its strong education institutions, multiculturality and liberal post-graduate work permits, is expected to attract even more students from India post the pandemic, as Australia and New Zealand remain shut, and several prospective students drift elsewhere.[11] This might become a wider trend extending to other countries from South Asia with high outbound students, such as Nepal and Bangladesh. Indeed, with an accommodating policy enabling neighbouring South Asian students to come in, India too can significantly enhance its intake of inbound students.

Conclusion

Student movements within the Asia-Pacific region reflect strong tendencies to move out on part of several countries. China, India, Vietnam, and Nepal are the most prominent among these. South Asian region, as such, has a large number of outbound students. Many of these students travel to countries within the Asia-Pacific, such as Australia and New Zealand, which are big draws for not just students from South Asia, but also from East and Southeast Asia. The pattern of outbound student movements, however, might change following the outbreak of COVID-19. Most of the Asia-Pacific sub-regions continue to retain strong border restrictions as they struggle to stamp out the latest surge of COVID-19 infections. These restrictions could encourage students, particularly from India and the rest of Southeast Asian region, to look for other higher studies options, particularly in the West. Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and the Middle East have begun the process of getting students back on campus for the upcoming academic years and prospective students from South Asia are likely to look at these destinations more closely, with the opening up in the Asia-Pacific remaining uncertain.

If the trend indeed perpetuates, it might reflect in the medium term on prospects of current regional higher education export hubs. Regions like Oceania and parts of Southeast Asia with high student mobility ratios (Table 1) due to their ability to attract large numbers of inbound students might not remain as prominent exporters of education services, as they are now. Shifting preferences of South Asian students beyond the Asia-Pacific might heavily influence this change.

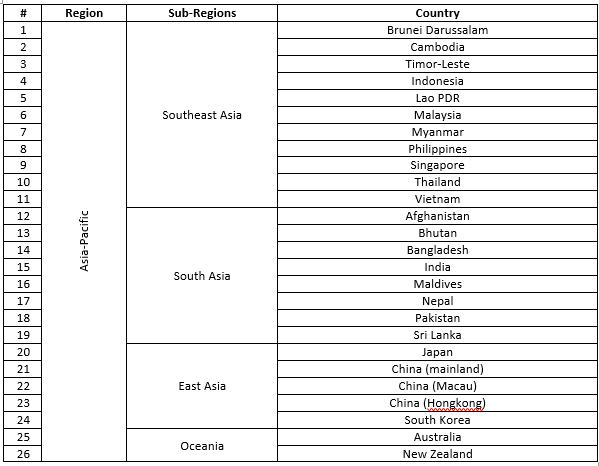

Appendix 1: List of countries in the Asia-Pacific and its sub-regions

Note: Inward bound/Immigrating students come into a country/region (destination) for tertiary studies and are captured by the metric ‘Where do they come from’ in the database. Outward-bound/emigrating students leave a country/region for tertiary education and are captured by the data metric ‘Where do students go to study’.

Source: http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow

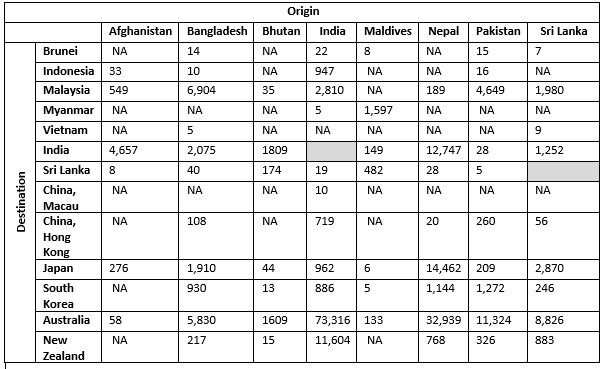

Appendix 2: Movement of students from South Asia to the Asia-Pacific

Note: ‘Origin’, as described in the columns, are South Asian countries. ‘Destination’ (rows) are countries they are travelling to, including in South Asia.

Source: http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow

. . . . .

Dr Amitendu Palit is a Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Trade and Economic Policy) at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasap@nus.edu.sg. Ms Divya Murali is a Research Analyst at the institute. She can be contacted at divya.m@nus.edu.sg. Ms Mekhla Jha is a student research assistant at the Institute. She can be contacted at mekhla.jha@u.nus.edu. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] Services exports are broadly divided into four categories or modes of delivery. These are cross-border supply (mode 1), consumption abroad (mode 2), commercial presence (mode 3) and presence of natural persons (mode 4). Mode 2 refers to service deliveries when the consumer of the service travels to another location for obtaining the service and pays for it. See Kurt Larsen, John P Martin, and Rosemary Morris, ‘Trade in Educational Services: Trends and Emerging Issues’, Working Paper, OECD, May 2002, for a useful classification of trade in services and educational services, https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/2538356.pdf.

[2] Student mobility ratio for a country is computed as the ratio of its total inbound students and outbound students.

[3] Student movement ratio greater than one for a country/region indicates the number of incoming students to be higher than the outbound ones. Countries with student mobility ratios less than one are those where outbound students are more than incoming students.

[4] ‘Global Flow of Tertiary-level students’, UNESCO Institute of Statistics, http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student -flow. The data was published in September 2019.

[5] SIPI = {Inbound students from within Asia-Pacific /Global Inbound students}. SEPI = {Outbound students from within Asia-Pacific /Global Outbound students}. The values of the indices range between 0 and 1.

[6] Lack of data on Singapore’s inbound students from the Asia-Pacific constrains a detailed opinion in this regard. However, the presence of large numbers of Chinese and Indian students in Singapore higher education institutions, coupled with Singapore’s overall high student mobility ratio, leads to the inference.

[7] ‘Indian students unable to reach Australia due to travel restrictions’, The Hindu, 22 June 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/indian-students-unable-to-reach-australia-due-to-travel-restrictions/article34914112.ece.

[8] ‘Canada remains top destination for Indian students, but travel restriction cause of concern’, The Times of India, 3 August 2021, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/nri/us-canada-news/canada-remains-top-destination-for-indian-students-but-travel-restriction-cause-of-concern/articleshow/84977202.cms.

[9] ‘Top 5 Study Abroad Destinations for Nepalese Students in 2021 – AECC Global Nepal’, AECC Global Nepal, 27 January 2021, https://www.aeccglobal.com.np/blog/top-5-study-abroad-destinations-in-2020.

[10] ‘UAE top spot for Indian students, Canada beats US to second place’, The Times of India, 15 August 2021, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/uae-top-spot-for-indian-students-canada-beats-us-to-second-place/articleshow/85339235.cms.

[11] ‘Canada remains top destination for Indian students, but travel restriction cause of concern’, The Times of India, 3 August 2021, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/nri/us-canada-news/canada-remains-top-destination-for-indian-students-but-travel-restriction-cause-of-concern/articleshow/84977202.cms.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF