Preserving Judicial Independence in India:

Need for ‘Cooling-Off’ Period for

Post-Retirement Appointments

Isha Gupta, Imran Ahmed

8 June 2023Summary

The independence of the judiciary is a key underpinning of India’s constitution and its democracy. The lack of a ‘cooling-off’ period before the High Court and Supreme Court judges take on post-retirement political or government appointments sets a dangerous stage for conflicts of interest, lack of accountability, and a tarnished reputation of the judiciary and its independence.

An essential mechanism for holding the political executive accountable in modern democracies is by subjecting it to the scrutiny of other state institutions such as the judiciary. The separation between the executive and the judiciary is an indispensable element of the framework that guarantees a democratic government, not only for the present generation but also for future generations in India. According to the landmark Kesavananda Bharati versus State of Kerala (1973) case, the separation of powers between the legislature, executive and judiciary forms an integral part of the Indian constitution’s basic structure.

In 2014, immediately before the Narendra Modi government first came into power, former Chief Justice of India, P Sathasivam, took on the position of Governor of Kerala just four months after his retirement as Chief Justice of India. The decision was widely perceived as unusual and irregular, jeopardising the judiciary’s independence and setting a dangerous precedent for future judges where the government could exert influence on the Court by making post-retirement appointment offers to judges.

Numerous appeals have been made for the implementation of a mandatory interval, commonly referred to as a ‘cooling-off’ period before judges assume post-retirement positions. Cooling-off periods refer to a designated duration during which individuals are restricted from pursuing employment in a different sector. In India, various positions, both government and private, have varying mandated cooling-off periods. Retired civil servants from the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Police Service and Indian Forest Services cannot gain commercial employment within one year of retirement. On 29 May 2023, a plea was presented before the Supreme Court, seeking a two-year ‘cooling-off’ period for judges of the higher courts before accepting political appointments. The plea also urged the Supreme Court to advise retiring judges against accepting political positions until the plea is thoroughly examined.

The Bombay Lawyers Association, represented by its founder, President Ahmad Mehdi Abdi, filed the plea to safeguard the independence of the judiciary, uphold the rule of law and promote principles of reasonableness. Additionally, the plea aims to protect democratic principles and preserve the fundamental goals and ideals of the Indian constitution. It emphasises the vital role of the Supreme Court as the guardian of the constitution, highlighting the critical need for its impartiality. Ahmad pointed to the appointment of the former Supreme Court judge, Justice S Abdul Nazeer, as the governor of Andhra Pradesh on 12 February 2023 and noted that the acceptance of political appointments by judges from the Supreme Court and High Courts after retirement without ‘cooling-off’ periods blurs the lines between the executive and the judiciary. There is widespread concern that judges nearing retirement may deliver judgements that align with the government’s interests in order to secure favourable positions after their retirement. Even in the absence of a direct quid pro quo, if a judge rules in favour of the government in contentious cases and later accepts a post-retirement position, it could significantly impact public perception regarding the independence of the judiciary.

The outgoing Chief Justice, Justice R M Lodha, noted, “No Chief Justice of India, Supreme Court judge, a High Court Chief Justice or a High Court judge should accept any constitutional post or government assignment after retirement. In cases where there are statutes requiring a retired judge to head a tribunal or a commission, laws should be amended to make the cooling-off period mandatory.” Moreover, in recent years, there has been a growing trend of the boundaries between the judiciary and the executive becoming less distinct. In 2014, the executive was granted increased authority in the higher judiciary’s appointment process through a comprehensive overhaul, as outlined in the Constitution (99th Amendment) Act, 2014. Nevertheless, in 2015, the Supreme Court overturned this amendment, citing its infringement upon judicial independence.

However, the government has increasingly rejected the elevation of nominees considered politically or ideologically unfavourable. Petitions regarding delays in judicial appointments have been brought before the Supreme Court and remain an ongoing contentious issue. In this context, measures to insulate the judiciary’s independence from government interference appear even more necessary, a ‘cooling-off’ period for the post-retirement appointments for the judges being one of them.

. . . . .

Ms Isha Gupta is a research intern at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute in the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at isav17@partner.nus.edu.sg. Dr Imran Ahmed is a Research Fellow at the same institute. He can be contacted at iahmed@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

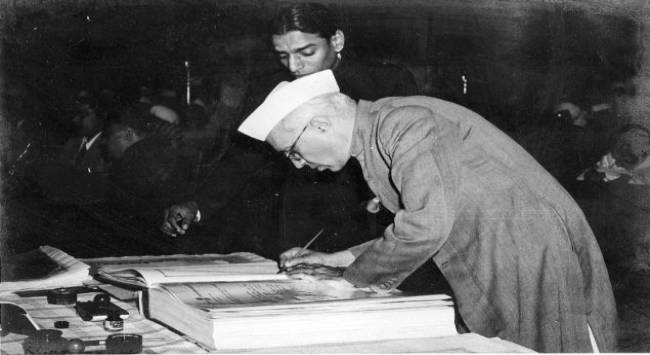

Pic Credit: Wikipedia Commons.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF