Summary

While conventional politics in India might have taken a backseat in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the way the crisis is being handled is itself intensely political. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s handling of the crisis has enhanced his popularity but there have been questions on the plight of migrant workers and the operation of Indian federalism. The long-term impact of COVID-19 though might be felt most in the expansion of the state, the centralisation of power and the measures rolled out to tackle the fallout of the pandemic.

There is little consensus on the kind of politics that COVID-19 will trigger in India. In the wake of the pandemic, some commentators have pointed to a temporary abatement of conventional politics in India. However, the way the crisis is being handled is itself intensely political. There is a concerted effort by the central government to show that the pandemic, particularly the number of infections and fatalities, is under control. The state governments are also doing the same.

Surveys show that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s handling of the crisis and the imposition of a national lockdown have enhanced his popularity at a time when he was confronting an economic slowdown and protests over the Citizenship Amendment Act. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has not passed up the opportunity to publicise the positive ratings with Home Minister Amit Shah tweeting that Modi was way ahead of other global leaders in this regard. However, there has been a clear class bias in the government’s decision making. The poor and marginalised have borne the brunt of the lockdown with thousands of migrant workers initially stranded in their place of work or on highways.

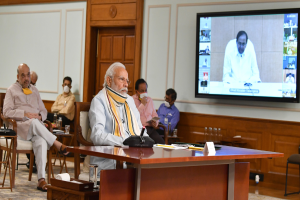

Modi has used the opportunity to address the nation on multiple occasions. By labelling the threat of the virus as a war, demanding sacrifices of the Indian people and invoking the Mahabharata, Modi has adroitly rallied the country around the flag. Modi has also used the pandemic to show that he can effortlessly make the Indian public bend to his will.

The handling of the pandemic has thrown the spotlight on Indian federalism. Despite health coming under the purview of the states, the Centre has used the National Disaster Management Act to impose a nationwide lockdown from 24 March 2020. While most state governments have toed the central line, some have been pulled up for deviating from the national policy. Indeed, opposition-ruled states like West Bengal – where Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee is the strongest critic of the Modi government and where elections are due next year – have been singled out for criticism. Some states, on the other hand, have criticised the Centre for prohibiting the sale of liquor, one of the biggest sources of revenue, during the lockdown’s first phase.

There has been a wide variation too in the response of the different Indian states to the pandemic. States like Kerala, with its strong public healthcare system and high levels of literacy, have tackled the pandemic well while others have been laggards. A study has shown that the case fatality ratio was the lowest in Kerala and the highest in states like Maharashtra, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. The rate of testing, the enforcing of social distancing and health infrastructure possibly explains the variation.

There are parallels between the lockdown announcement and Modi’s dramatic decision on demonetisation in 2016. As in demonetisation, the hardest hit by the lockdown have been the poor, migrant labourers and daily wage earners, for whom no measures were initially put in place. It was only when the media and some Chief Ministers highlighted the plight of India’s internal migrants did the Indian state provide succour, first for shelter and food, and later transportation. The skewed impact of COVID-19 has similarities with the 1918 Spanish flu, which inordinately affected the poor and rural India.

In the current context, the impact of the pandemic might be felt most in the expansion and reach of the state and the centralisation of power. Both these trends had been visible in India over the past few years but the pandemic is likely to accentuate them. For one, the enormous increase in state surveillance in the wake of the pandemic, which has happened worldwide, is unlikely to be rolled back in a hurry. More significantly, we are likely to see a much bigger role for the state and state-owned enterprises. Contrary to what many saw as the free market and reformist leanings of Modi in 2014, he has shown little inclination to cut the bloated Indian state to size.

Centralised decision-making is also likely to outlive the pandemic. Modi’s decision to impose a nationwide lockdown came at a few hours’ notice and there was no evidence to show that he had consulted widely. Some Chief Ministers complained that had they been taken into confidence before, and not after, the Prime Minister’s decision, the situation might not have been so dire regarding the migrant labourers. It was only after the lockdown announcement that Modi consulted with Chief Ministers and gave federalism its belated due. Indeed, some have pointed out this was astute politics with Modi taking credit for the lockdown, leaving the Chief Ministers to tackle the messy aftermath of the exit strategy, which has proved to be a bureaucratic nightmare. Going ahead, India’s federal structure is likely to face political and financial stress.

Finally, the impact of the economic package announced by Modi on 12 May 2020 will be something to watch. Leaving aside the economic ramifications, Modi’s call for an ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (Self-reliant India) is of particular interest. Whether it remains just a slogan or charts a new path, different from earlier versions of ‘Swadeshi’ (self-reliance), will be a critical feature of the remainder of Modi’s second term.

Modi has shown that he is willing to disrupt or rewrite the traditional rules of politics in India. The pandemic’s aftermath will be a test of Modi’s governance.

. . . . .

Dr Ronojoy Sen is a Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Politics, Society and Governance) at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasrs@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF