India-Australia Trade Deal: Realistic Ambitions and Flexible Negotiations

Amitendu Palit

16 August 2021Summary

India and Australia are resuming talks on a bilateral trade deal after several years. Close strategic proximity between the two countries, following the COVID-19 pandemic, imparts strong purpose and political willingness for the deal. A deal is eminently possible if ambitions are realistic and negotiations flexible.

After staying suspended for six years, talks are being revived on a bilateral free trade deal between India and Australia. The impetus arises from the growing strategic closeness between the two countries, particularly after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Driven by wariness over an assertive China, India and Australia have been expanding cooperation across the Indo-Pacific region and within key geo-economic forums like the Quad. Both countries have committed to working with the United States and Japan on the production and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines and creating standards for critical and emerging technologies through the Quad partnership. They are also working with Japan on enhancing resilience of regional supply chains through the supply chain resilience initiative.

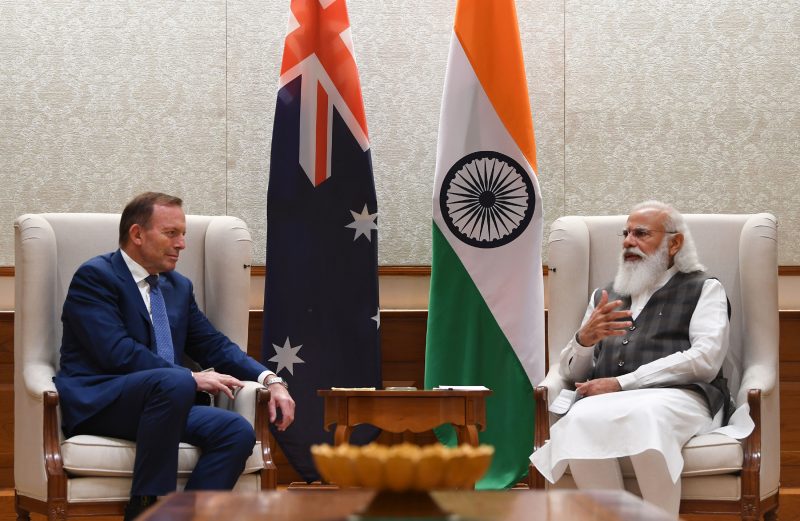

The recent acceleration in strategic bonding between India and Australia has been accompanied by a visible escalation in political will to work on a trade deal. The appointment of former Prime Minister Tony Abbott by Australia’s Scott Morrison administration to lead the process is a distinct example of the strong political will. The Abbott administration was positively inclined towards such a deal and was instrumental in talks with India progressing a long way before they got stuck in 2015. The political signal from Abbot’s appointment comes at a time when India too is trying to turn a new leaf by engaging in free trade agreements and shedding its earlier reticence as indicated by its commerce minister, Piyush Goyal.

From a purely trade negotiating perspective, practically nothing has changed since the talks were stalled. Negotiations, therefore, will encounter the old sticky issues. India would face demands for tariff cuts in a large number of products that are of interest to Australia. These include dairy, fruits and vegetables, cereals as well as sugar and confectionaries, where India’s applied tariffs are more than 30 per cent. These tariffs are far higher than those that Australian exporters of these items face in the Chinese market. Indian negotiators would have to overcome stubborn domestic resistance to cut these tariffs. On their part, Australian negotiators would need to convince their Indian counterparts about the access that Indian professionals would get in the Australian domestic market. In this regard, India would want to be assured about the federal commitments in the trade deal being honoured by provinces too.

The challenge for the negotiations would be to not get stuck in the difficulties and stay focused on a purposeful outcome. The current geo-economic context should help in doing so. The increasingly favourable geo-economic context of recent years has underpinned the urgency of greater economic engagement between the two countries. This has led to initiatives like economic strategy reports by both countries on trade and investment prospects with respect to each other. The perspectives have been encouraged by the harsh reality of the need for bilateral trade relations to reduce economic dependence on China.

A trade deal is eminently feasible if it does not get bogged down in negotiating stubbornness and the unwillingness to compromise. Talks must be held with the non-negotiable goal of reaching a deal. The commitment needs to be greater from India in this regard. India’s last-minute jettisoning of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in November 2019, which includes Australia too, would cast doubts over its willingness to go the full distance on the deal. India must display commitment to conclude a deal to dispel these doubts.

Negotiators of both sides should be realistic in their ambitions. A trade deal need not obtain complete commitment to all market access in one go. A clear distinction between market access targets that are ‘easily achievable’, ‘difficult, but possible’, and ‘tough, not worth it now’ can help in shaping much of the trade deal quickly.

Talks must also eschew unproductive negotiating nuances. For example, there is little point in wasting negotiating time on deciding whether a ‘negative list’ (preferred by Australia) or a ‘positive list’ (preferred by India) approach should be the basis to discuss services trade commitments.

A deal that focuses on achievable market access targets with a set of trade and investment standards in areas where both countries are keen to collaborate, such as supply chains, education, finance, critical technologies, minerals and clean energy, should be a wholesome outcome. With flexible negotiations, the political will mustered by both sides can clinch such a deal.

. . . . .

Dr Amitendu Palit is a Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Trade and Economic Policy) at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasap@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: pmindia.gov.in

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF