Foreign Exchange Woes in South Asia –

Are there Further Currency Crises Threats?

Deeparghya Mukherjee

28 July 2022Summary

Over the last few years, the global economy has been subjected to multiple shocks which have affected global commerce and could adversely affect the economies of various countries. This paper aims to investigate the recent trends in foreign transactions at a country level and the foreign reserves position of the South Asian countries to understand the risk of currency crashes or the need for caution towards bailout packages.

The Faltering World Economy

The world economy has faltered while trying to recover fully from the global economic slowdown in 2008-09. Ramifications of the slowdown manifested themselves in various forms in the immediate aftermath. Though some of the advanced countries started recovering, post-2016, the United States (US)-China trade war had implications for not only the US and China but for many other countries linked to the US-China trade. Global trade and commerce were hurt significantly, and protectionism had been on the rise in various countries, with the multilateral trading system suffering across the world. Few countries, at best, could remain free from the effects of the trade war, given that most trade happens through production networks running as a complex chain across multiple countries.

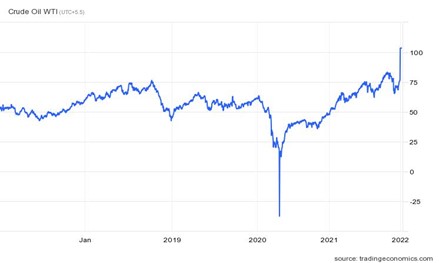

The above challenges notwithstanding, the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit the world in late 2019, brought the world to a standstill, stalling international trade and commerce like never before. Restrictions on international travel, globally enforced lockdowns, closures in ports and container shortages and the non-availability of drugs to cure COVID-19 brought the world to a grinding halt, making working from home the norm than the exception. At the height of the COVID-19 crisis, around the middle of 2020, the world witnessed all-time lows in oil prices.

Figure 1 shows the movement of oil prices till before 2022. It reveals that while the prices were reasonably steady till about 2019, they hit rock bottom in the middle of 2020 when most nations around the world were into national lockdowns and after that, oil prices started increasing, and as we entered 2022, prices were spiralling up higher along with rising tensions of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Figure 1: Oil price movements till the beginning of 2022

Source: tradingeconomics.com

The above developments significantly impact emerging and developing economies in particular. Most emerging economies need to import critical inputs for their economies, starting with oil to technology-intensive parts and components. They must also service foreign loans obtained for infrastructure development or other foreign investments in several business ventures. These require precious foreign exchange. To make good on these commitments, it’s crucial to earn foreign exchange. The principal source is export earnings or foreigners’ investments in the country, which are linked to perceptions of the country’s growth potential.

South Asian Economies, through the Pandemic

All the South Asian countries are either emerging or developing economies. With the onset of the pandemic and the need to impose lockdowns, domestic production has gone down, and exports have suffered globally, bringing down the export earnings of all countries. It has further dampened expectations of growth. The two effects have brought down foreign exchange earnings for countries, first, due to dampened exports and second, due to lower inward foreign investments with lower growth expectations due to perceived uncertainties.

Before proceeding further, we take note that foreign exchange position and movement of foreign currency exchange rates are critically linked to two other important economic variables: i) domestic inflation rates; and ii) interest rates, both managed by the central bank of a country. The higher the domestic inflation relative to trading or business partner countries, the greater the prices of exportable and demand for importable. Both effects lead to a higher relative demand for foreign currency depleting reserves and leading to currency depreciation. The higher the domestic interest rate, the higher the cost of doing business (borrowing capital), but the greater the return on investment for foreign providers of capital, leading to more significant inflows of foreign currency appreciating the exchange rate and thereby strengthening the foreign currency reserves position.

We analyse the possible risk of the South Asian countries entering into foreign exchange crises which lead to a default on foreign loans and massive loss of purchasing power of their currencies (quick large depreciations) through the movement of key economic metrics below. All statistics were collated from the world bank databank.[1]

Table 1 shows the reserves position of the countries in terms of the number of months of imports the reserves would be able to support. Rather than looking at reserves as a whole, we look at this metric as the value of reserves is only as good as the need for the country to import. Low reserves with high demand for import every month is catastrophic compared to high reserves with lower dependence on imports. Table 1 indicates that as of 2021, India maintained the healthiest record of reserves given its monthly import bills. The reserves could support almost 10 months of imports. The countries which were doing relatively poorly included Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

Table 1: Total reserves (months of imports)

| Country | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 9.77 | 11.83 | 12.13 | 12.18 | 13.75 | 16.63 | NA |

| Bangladesh | 6.83 | 7.60 | 6.77 | 5.68 | 5.86 | 8.66 | 6.29 |

| Bhutan | 9.61 | 9.44 | 9.89 | 7.90 | 9.99 | 13.26 | NA |

| India | 8.00 | 8.43 | 8.16 | 6.90 | 8.27 | 12.93 | 9.83 |

| Maldives | 2.17 | 1.57 | 1.81 | 1.85 | 1.94 | 4.27 | 2.42 |

| Nepal | 12.53 | 10.29 | 9.35 | 6.61 | 7.46 | 12.48 | 6.75 |

| Pakistan | 4.43 | 4.59 | 3.15 | 1.91 | 3.08 | 3.87 | 3.36 |

| Sri Lanka | 3.48 | 2.80 | 3.42 | 2.82 | 3.36 | 3.30 | NA |

Source: World Bank databank

Given the above, the reserves also get drained as the countries need to service short- and long-term loans taken earlier from abroad. The higher the incidence of short-term loans which require servicing, the higher the pressure on reserves in the immediate future and hence, the greater the risk of default and currency crashes. Looking at the short-term debt that various South Asian countries had to service with the reserves in Table 2, the poor performers in this were Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the Maldives and, to some extent, Bangladesh. Amongst these countries, the condition of Sri Lanka and Pakistan worsened significantly between 2017 and 2020. Sri Lanka especially has been at high risk since 2020.

Table 2: Short-term debt (% of total reserves)

| Country | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 4.1 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 4.4 |

| Bangladesh | 24.1 | 24.3 | 32.2 | 28.2 | 29.8 | 25.4 |

| Bhutan | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| India | 23.1 | 23.2 | 23.7 | 26.0 | 23.0 | 17.5 |

| Maldives | 27.9 | 27.8 | 19.0 | 33.5 | 44.7 | 35.4 |

| Nepal | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 3.1 |

| Pakistan | 41.8 | 41.3 | 77.6 | 116.4 | 100.1 | 81.3 |

| Sri Lanka | 103.9 | 123.4 | 100.7 | 118.2 | 110.4 | 148.2 |

Source: World Bank databank

Having looked at the reserves position of the South Asian countries, to understand the possibility of trouble further, one needs to look at the trade patterns (excessive imports) and domestic inflation and portfolio inflows. Imports in excess of exports would signal a drain in foreign currency which could deplete reserves, and higher domestic inflation would have two effects – substituting domestic consumption with foreign goods (which are relatively cheaper) and lower export potential – both leading to lowering reserves and further leading to a depreciatory pressure on the exchange rate. We find that Indian inflation was high in 2021 but Pakistan had seen the highest inflation levels in South Asia starting in 2019 which exceeded 10 per cent in 2021. This trend is closely followed by Sri Lanka, which saw an inflation rate of eight per cent in 2021.

Looking at the trade balance (Table 3), one finds that India has run the highest merchandise trade deficit, but the condition is bad for Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. However, India always maintains a surplus in services trade which would make up for the deficit in merchandise trade. Additionally, India receives a healthy inflow of portfolio investments (Table 4), once again cushioning its foreign exchange positions. Amongst the other South Asian countries, given that Bangladesh has done better in inflation management, it would stand out better than others, given its reserve cover for imports and a manageable short-term debt to be serviced by reserves.

Table 3: Trade balance (in US$ billion)

| Country | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bangladesh | -14.5 | -10.3 | -13.2 | -22.5 | -18.6 | -19.0 | -23.9 |

| Bhutan | -0.6 | -0.5 | -0.5 | -0.5 | -0.3 | -0.4 | 0.0 |

| India | -48.3 | -47.9 | -112.5 | -108.2 | -120.4 | -81.1 | -144.9 |

| Maldives | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | -0.1 | NA |

| Nepal | -6.4 | -7.1 | -9.5 | -11.6 | -12.3 | -9.6 | -11.9 |

| Pakistan | -17.4 | -25.3 | -34.8 | -41.9 | -43.3 | -38.7 | -41.1 |

| Sri Lanka | -6.1 | -8.0 | -8.5 | -8.9 | -6.0 | -5.0 | -4.6 |

Source: World Bank databank

Finally, net portfolio equity inflows reveal the confidence of external investors in an economy’s growth potential and clearly indicate how robust the foreign exchange position should be in short to medium term. India has been the highest recipient of portfolio inflows, insulating it from major foreign exchange risks until before 2022. However, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan have seen outflows of portfolio equity capital. Given their positions of foreign exchange and debt servicing requirements, this would not serve them well if there were added risks to the global economy starting in 2022. We do not have data for portfolio equity flows for Afghanistan, Bhutan and Nepal.

Table 5: Portfolio net equity inflows (in US$ billion)

| Country | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bangladesh | -0.10 | 0.11 | 0.26 | -0.03 | -0.07 | -0.35 |

| Bhutan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| India | 1.93 | 2.34 | 5.93 | -4.36 | 13.77 | 24.85 |

| Maldives | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.11 |

| Nepal | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pakistan | 0.53 | -0.34 | -0.39 | -0.53 | 0.02 | -0.54 |

| Sri Lanka | -0.06 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.22 |

Source: World Bank databank

Based on the figures and our analyses, as of the beginning of 2022, Pakistan has been at the greatest risk of facing external economic problems given its foreign debt situation, foreign currency reserves and domestic inflation. The currency thus faces the risk of massive depreciation if not supported by external forces.

Economic Challenges in 2022

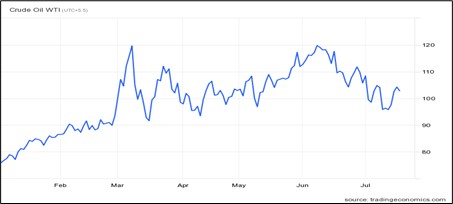

The year 2022 began with rising tensions between Russia and Ukraine, followed by the war creating issues worldwide. Specific focus may be put on the movement of oil prices. Further to the sharp increase in oil prices towards the end of 2021 (as seen in Figure 1), we have now observed a consistent increase in the price of crude oil, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Crude oil prices (2022)

Source: tradingeconomics.com

Additionally, in various economies, as COVID-19 started getting accepted as a way of life with vaccinations having gathered enough steam reigning in the risks of possible loss of life, the pent-up demand hit the markets without adequate ability to respond through instantaneous adjustments in supply. This has been true, especially for the advanced economies, where this has spiralled up inflation, further fanned by rising oil prices.[2]

If we look at inflation levels in South Asia in most recent times, Pakistan clocked a rate of 21.32 per cent in June 2022 which is the highest for the country in the last 13 years.[3] Bangladesh’s inflation too has been rising of late and hit 7.56 per cent in June 2022 (almost double what it was in 2021).[4] India has managed an inflation rate of around seven per cent more recently; however, pressures remain and the Reserve Bank of India has increased rates recently to help contain inflation. Sri Lanka is currently experiencing food inflation of 80 per cent, with overall inflation of 55 per cent.[5] Nepal has clocked an inflation rate of 8.6 per cent in June 2022, significantly higher than what it was till 2021.

Coming to the possibility of foreign exchange outflows, the situation in Pakistan and Sri Lanka is particularly worrying. Pakistan has already started blocking the outflow of dollars through capital controls, and the exchange rate has slid to PKR226 per US dollar at the time of writing the article.[6] These are in the face of delays in approval and disbursement of US$1.12 billion (S$1.55 billion) by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[7] Pakistan’s external debt position is in excess of US$128 billion (S$177 billion), the highest the country has seen in recent times, and foreign exchange reserves have dipped below US$10 billion (S$14 billion).[8] Sri Lanka is staring at an external debt of US$50 billion (S$69 billion) with reserves drying up and has already hit the currency crisis stage.[9] India’s external debt is US$621 billion (S$858 billion). With a foreign exchange reserve position of US$580 billion (S$802 billion) this month, India is currently comparatively safer and perceived currency risks are exaggerated at best. In June 2022, the country’s foreign exchange reserves stood at US$41.8 billion (S$58 billion) in Bangladesh, and the external debt was around US$91 billion (S$126 billion). Hence, reserves fall short of external commitments.[10] The country has already put capital controls on not allowing imports and curbs on officials’ foreign visits.

Nepal has foreign exchange reserves of around US$9 billion (S$12.4 billion), and its recent external debt estimates stand at around US$9 billion (S$12.4 billion).[11] With the rising inflation, Nepal would need to be careful, and the central bank’s action of increasing rates may help possibilities of capital flight from the country. The Maldives’ foreign exchange reserves stood at US$756 million (S$1 billion)[12] earlier this year, and the external debt is far in excess of the reserves. Most global agencies are sceptical about the potential of the Maldives to overcome the stress and pay back even as it is scheduled to be one of the fastest growing economies in 2022.

Given the detailed analyses above, we conclude that while Sri Lanka has already entered the phase of political and economic crises, Pakistan’s fate is critical. Without further injections of foreign capital from the IMF or Countries like China, Pakistan could enter a similar situation to Sri Lanka. The Maldives and Nepal, while critical, may save up with growing pent-up tourism demand. Bangladesh may need to be careful in controlling inflation and facilitating remittance inflows to avoid moving to the edge. Finally, to help the situation, oil prices need to stabilise with the growing ability to export of these nations.

. . . . .

Dr. Deeparghya Mukherjee is an Associate Professor of Economics at the Indian Institute of Management Nagpur and an Academic Visitor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. He can be contacted at deeparghya@iimnagpur.ac.in. The author bears full responsibility for the facts and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] For data source for all statistics from tables 1 to 5 see “Word Bank databank”, The World Bank, https://databank.worldbank.org/home.aspx.

[2] For a detailed analysis of reasons behind inflations across the world, see “The return of Global Inflation”, The World Bank, https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/return-global-inflation.

[3] Carmen Reinhart and Clemens Graf Von Luckner, “Pakistan inflation accelerates to 21.32%”, The World Bank, 14 February 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-01/pakistan-inflation-accelerates-to-21-32-in-june-on-costly-oil.

[4] “Bangladesh Inflation Rate”, Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/bangladesh/inflation-cpi.

[5] “CCPI based headline inflation recorded at 54.6% on year-on- year basis in June 2022”, The Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 30 June 2022, https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/news/inflation-in-june-2022-ccpi.

[6] Shabaz Rana, “SBP restricts outflows of dollars”, Tribune, 19 July 2022, https://tribune.com.pk/story/2366631/sbp-restricts-outflow-of-dollars.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Pakistan Total External Debt”, Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/pakistan/external-debt.

[9] Krithiga Narayanan,“Sri Lanka’s foreign debt default: Why the island nation went under”, Deutsche Welle, 14 April 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/sri-lankas-foreign-debt-default-why-the-island-nation-went-under/a-61475596.

[10] “Bangladesh external debt”, CEIC, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/bangladesh/external-debt.

[11] “Nepal External Debt”, CEIC, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/nepal/external-debt.

[12] Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/.

Image 1: Financial Crisis, Pixabay

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF