Summary

In an attempt to bring about transparency and mitigate the prevalence of cash donations to political parties, the government introduced the scheme of electoral bonds in 2018. However, the scheme has evoked negative response. Issues regarding anonymity around donors, removal of the ceiling on amounts that corporate entities could donate and cornering of large chunks of donations by the government in power have evoked litigation in the Supreme Court. The Court is to announce its verdict which is set to have a serious bearing in the 2024 general elections.

As a part of the Union budget of 2017, the Indian government announced a scheme for the issuance of electoral bonds which donors could purchase from designated banks. This announcement was an attempt to cleanse politics of money power. Electoral Bonds, introduced in 2018, are interest-free bearer bonds or money instruments that can be purchased by companies and individuals in India from authorised branches of the State Bank of India. The bank is obligated to disclose the details following only upon a court order or a requisition by the law enforcement agencies. Before the scheme was introduced, political parties had to make public all donations above ₹20,000 (S$320). Also, no corporate entity was allowed to make donations amounting to more than 7.5 per cent of their total profit or 10 per cent of revenue. These donations had to be reported to the Election Commission without which no tax rebate could be extended. On the other hand, electoral bonds permit donations of ₹20 million (S$320,000) or even ₹2 billion (S$32 million) to be made anonymously on the rationale that donors desired secrecy.

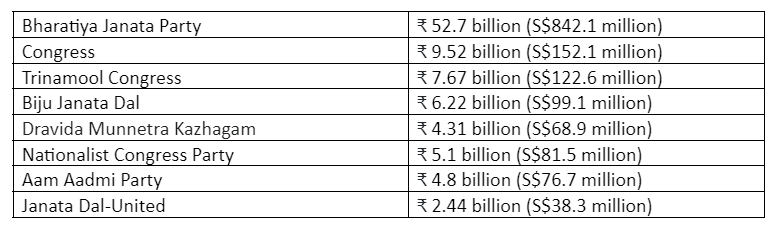

Though the electoral bond scheme was ostensibly introduced to provide transparency and do away with cash donations to political parties, issues of anonymity around donors have emerged. The removal of the earlier requirement of an enterprise disclosing the name of the political entity to which the contribution is made was also creating disquiet in the minds of the people. Given their dominance over the economic and administrative apparatus and the greater chances of capturing political power, the large and established parties have drawn undue advantage from the new measures. Citing such inefficiencies in the electrical bond system and quoting the skewed pattern of fund flow as illustrated below (where 57 per cent has gone to the Bharatiya Janata Party), public interest litigations were filed challenging the validity of the scheme. These cases had been pending in the Supreme Court for eight years, and only in October 2023, the Court referred the challenge to a Constitution Bench of five judges.

Bond Funding

The total value of electoral bonds sold from 2017-18 to 2021-22 is ₹92.08 billion (S$1.48 billion). The party-wise breakdown is at Table 1.

Table 1: Total value of electoral bonds – party-wise (2017-18 to 2021-22)

Source: Damini Nath, “57% vs 10%: BJP vs Congress share in electoral bond funds”, Indian Express, 1 November 2023, https://indianexpress.com/article/political-pulse/57-vs-10-bjp-vs-congress-share-in-electoral-bond-funds-9007429/

The government maintains that the electoral bonds scheme floated by the centre does not impinge upon any existing right of any person and cannot be said to be repugnant to any fundamental right. The government also maintains that confidentiality is the heart and soul of the scheme and necessary to achieve the objective of utilising clean money for political donations. The concept of ‘free and fair elections’ is furthered by allowing the persons to make donations without having to be worried about censures, reprimands or retaliation by the stakeholders.

Petitioners before the Court have argued that the problem with the scheme is that it provides for selective anonymity. It is not confidential qua the bank or the law enforcement agencies. The doubt is whether the confidentiality clause is paving the way for a quid pro quo, or in other words, even giving rise to a possibility of legalising kickbacks or legalising the motive for the donation to the fund. Another negative arising from the scheme is that by donating to electoral bonds, the company has no guarantee that the money is actually being spent on elections. It may well be spent by the party receiving the bond money on building party infrastructure.

The government has taken the stand in court that potential abuse cannot be a ground to hold the scheme bad in law when it is really designed to move cash-driven political donations to formal banking channels. Petitioners cannot demand access to the information on each and every political donor and contribution since it is third-party information which is not even disclosed to the government. The government maintains that the right to information and transparency cannot be pressed against non-state actors for information which is not even in the knowledge of the state.

During the course of the hearing, the Court, however, repeatedly pointed out that although the emphasis on reducing the cash element in the electoral process by encouraging the use of authorised banking channels was a laudable objective, the electoral bond scheme appeared not to augur well with the need of transparency or to avert the possibility of such donations being kickbacks in reality. The bench, in fact, went on to suggest that the centre could consider a scheme where all donations be handed over to the Election Commission of India for distribution to the parties concerned. To take forward its point on legitimising kickbacks through the scheme, the bench said that prior to the electoral bond scheme, there was a requirement under the Companies Act that political donations could only be given up to 7.5 per cent of net profit by a company.

The case, pointing out various inadequacies in the scheme, has been reserved for orders and its outcome is expected to have a significant bearing on the Lok Sabha elections scheduled to take place next year.

. . . . .

Mr Vinod Rai is a Distinguished Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute in the National University of Singapore (NUS). He is a former Comptroller and Auditor General of India. He can be contacted at isasvr@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF