Decline of the Congress: The Impact of Defections and Breakaway Factions

Ronojoy Sen, Srishti Gupta

11 November 2020Summary

The Congress has been consistently losing leaders and members to the Bharatiya Janata Party over the past six years. This paper focuses on the issue of defections and traces the electoral fate of breakaway parties and defectors from the Congress in the post-‐1977 period in three states. The breakaway parties have either decimated the Congress or significantly reduced its strength in those states. There are no quick solutions to revive the Congress and stem defections, except for arduously rebuilding or reinventing the party.

Introduction

The regular bout of defections from the Congress over the past few years, including the drama over Sachin Pilot’s exit from and return to the Congress in Rajasthan, has led to two kinds of analyses. The first is on the deficiencies in the anti-‐defection law, which has been successfully exploited on several occasions since the legislation was passed. The second is the state of the Congress, which has been regularly losing leaders and members to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) over the past six years. This paper focuses on the latter issue and traces the electoral fate of breakaway parties and defectors from the Congress in the post-‐1977 period. The year 1977 has been chosen since that was the year when for the first time a non-‐Congress government – a coalition of parties under the Janata banner – was formed at the Centre.

In many ways, 1977 marked the beginning of the demise of the ‘Congress system’, as theorised by Rajni Kothari,1 which had already under stress from 1967, when for the first time, the Congress lost power in eight states. Kothari had famously described the Congress as a “party of consensus”, which functioned through an elaborate network of factions. The opposition groups in this formulation functioned as “parties of pressure”. Morris-‐Jones had described the phase from 1950-‐1967 in similar terms as “dominance coexisting with competition but without a trace of alternation.”2

Kothari, when he revisited the ‘Congress system’ in 1974, proposed that the system was still in operation, albeit in a much more complicated terrain, since there was still only one party of consensus and multiple oppositions.3 However, he admitted that after 1967, the Congress dominance was “strikingly diminished”. According to Subhash Kashyap, during the 10 years prior to 1967, there had been a total of 542 defections whereas in 1967 alone, there were 438 such cases. Several legislators had switched parties more than once and the actual acts of defection exceeded the 1,000 mark.4

Problem of Defections

Initial defections from the Congress have commonly been attributed to its character of a party associated with the freedom movement and a catch-all party. In the post-1967 period, the success of non-Congress parties at the state level, coupled with the Congress’ disinterest in forming coalition governments, meant that dissident Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) in the Congress could fulfil their personal interests and ‘ministerial ambitions’ elsewhere. In fact, 1967-68 was the first year when the Congress lost more defectors than it gained.5

A panel to examine the problem of defections, constituted under then Home Minister Y B Chavan, found that as many as 116 of the 210 defecting MLAs in the seven states that the Congress lost in 1967 were awarded with ministerial berths. This led, after two failed attempts, to the introduction of an anti-defection law in 1985, which laid the ground for disqualification of Members of Parliament (MPs) and MLAs. The law, however, protected legislators from disqualification in cases where there was a split with one-third of members leaving or merger with two-thirds of members of a legislature party joining another political party. Subsequently, the one-third split provision, which offered protection to defectors, was done away with. The anti-defection law not only slowed down individual defections,6 but also encouraged those wanting to defect to form regional parties.

After the Emergency, the Congress suffered its first major split in 1978, with members in favour of Indira Gandhi retaining the Congress presidency staying within Congress (I or Indira), and others forming a breakaway Congress faction, Congress (U or Urs), led by Karnataka Chief Minister Devaraj Urs.7

The following sections track the fate of breakaway units from the Congress in the states of Maharashtra, West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh.

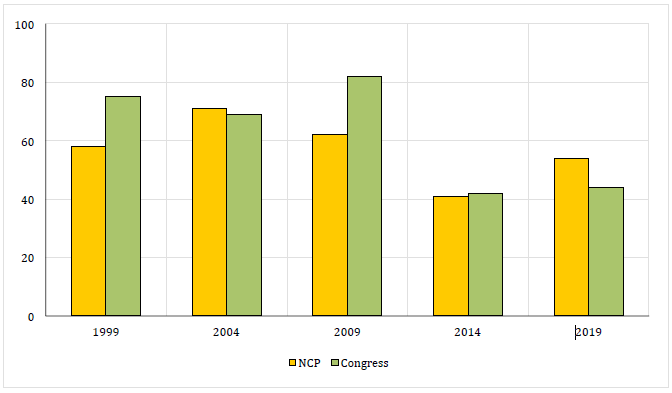

Maharashtra

One of Maharashtra’s tallest leaders, Sharad Pawar, took over the presidency of Congress (U) in 1981, renaming it Congress (Socialist). Although he was among the leaders who had broken away to Congress (U), Pawar had previously walked away with 38 Congress MLAs after Congress (U) and Congress (I) came together to form the government in Maharashtra in 1978. He successfully toppled the government by entering into an alliance with the Janata Party, thereby becoming the youngest chief minister of Maharashtra until his government was dismissed in 1980. Following the Maharashtra assembly elections of 1980 and 1985, Pawar remained the leader of the opposition, before returning to the Congress (I) in 1986. Pawar once again broke away from the Congress in 1999, primarily in opposition to the party’s projection of Sonia Gandhi as its president and prime ministerial candidate, and formed the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP). The NCP has since established itself as a major player in Maharashtra politics with a voter base comparable to that of the Congress. It has also entered into coalitions with the Congress to keep BJP-Shiv Sena alliance out of power (Figure 1). With the exception of 2014, when the BJP-Sena alliance won the polls, the NCPCongress coalition has formed the state government in 1999, 2004 and 2009. In 2019, the NCP and Congress allied with the Sena to form the government.

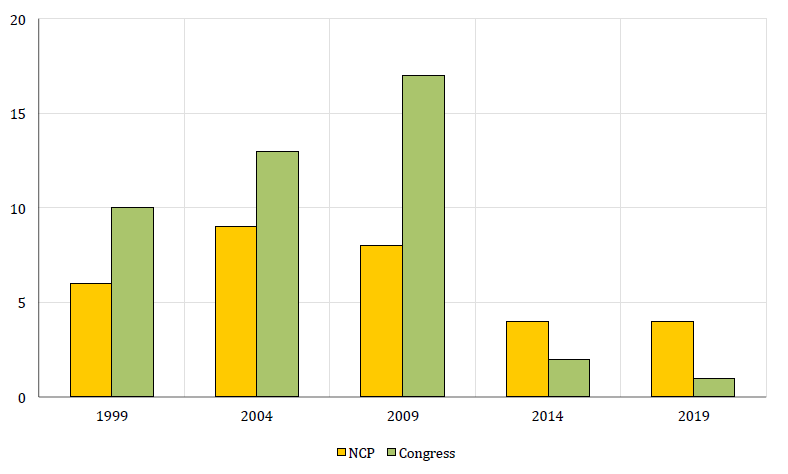

Figure 1: NCP vs Congress, Lok Sabha (Maharashtra)

Source: Election Commission of India (ECI)

The Lok Sabha results in Maharashtra over the years show different trends. Out of the 48 seats in Maharashtra, the highest the NCP has ever won was nine seats in 2004, which were then reduced to four seats in both 2014 and 2019 (Figure 2). The Congress won about a third or more of the remaining seats until 2014, when it was reduced to just two seats.

In 2019, Congress won only one seat in Maharashtra. Pawar himself has long been a member of the Lok Sabha between 1991 and 2014, and a Rajya Sabha MP since, in addition to holding ministerial berths at the centre as a United Progressive Alliance coalition member between 2004 and 2014.

Figure 2: NCP vs Congress, Maharashtra Assembly Elections

Source: ECI

West Bengal

West Bengal’s current chief minister, Mamata Banerjee, severed ties with the Congress in 1998 after having served as a Congress MP for two terms: from Jadavpur in 1984 and Calcutta South in 1991, during which she also briefly served as a minister.8 The Trinamool Congress Committee, a faction that Mamata had been steering parallel to the West Bengal Congress since the early 1990s, formalised into the Trinamool Congress (TMC).

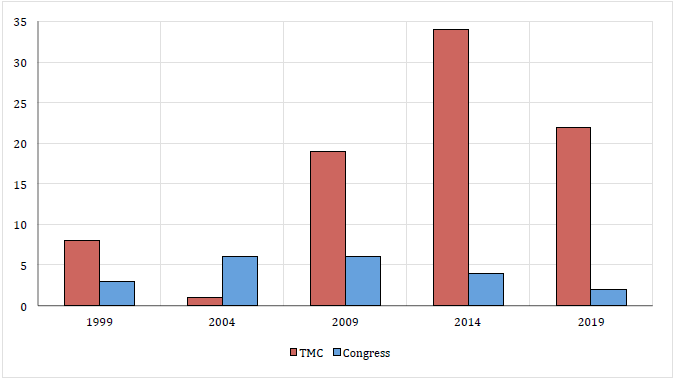

The TMC took part in its first Lok Sabha elections in 1999 and won eight seats out of the 28 that it contested. The Congress, on the other hand, could manage only three of the 41 seats that it contested (Figure 3). With the exception of the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, when the Communist Party of India (Marxist) swept the polls in West Bengal, the TMC has had a significantly better electoral showing compared to the Congress in the general elections. In 2014, the TMC won 34 of the 42 Lok Sabha seats in West Bengal, increasing its seat share by 15 seats from 2009. The Congress’ seat share fell by two seats from 2009, and was reduced to four in 2014, and to two in 2019. The TMC too suffered a loss in seat share in 2019 when its tally fell to 22, while the BJP increased its seat share to 18 from only two in 2014.

Figure 3: TMC vs Congress, West Bengal Lok Sabha

Source: ECI

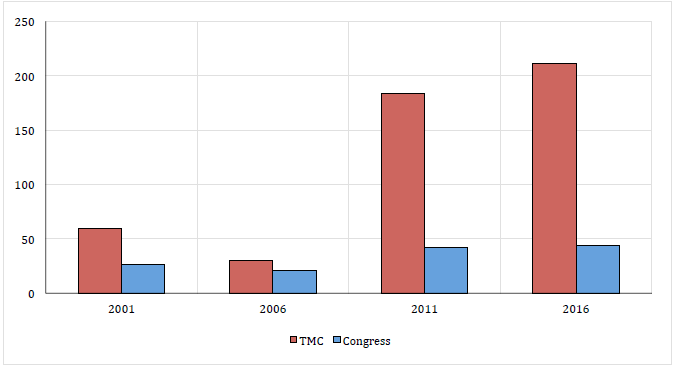

In the Assembly elections, the TMC, in an on-and-off alliance with the BJP/National Democratic Alliance, failed to gain ground both in 2001 and 2006, against the Left Front’s dominance.9 However, with the TMC increasing its support base in rural Bengal, the Left’s vote share in the 2008 panchayat elections in West Bengal plunged from previous highs of up to 90 per cent to a mere 50 per cent.10 Consequently, the TMC increased its seat share in the 2009 Lok Sabha elections as well, with Banerjee herself being briefly appointed the central railway minister. Shortly after, the TMC, although in a pre-poll alliance with the Congress, singlehandedly won a majority in the 2011 assembly elections with 184 seats, ending the Left Front’s 34-year-long rule in the state (Figure 4). The TMC further increased its seat share to 211 in the 2016 assembly elections, with Banerjee serving as chief minister for both terms.

Figure 4: TMC vs Congress, West Bengal Assembly Elections

Source: ECI

Andhra Pradesh

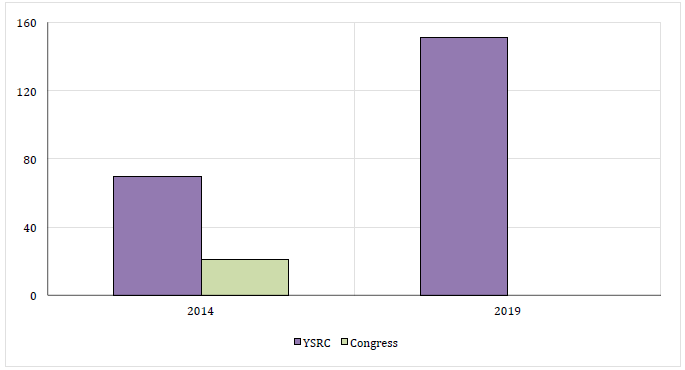

One of the more recent instances of a significant breakaway from the Congress has been that of Jagan Mohan Reddy in Andhra Pradesh. In the wake of the death of his father Y S R Reddy (YSR), then chief minister of Andhra Pradesh, in 2009, Jagan was antagonised by how the Congress high command quickly side-lined him and YSR’s legacy, and resigned to form the YSR Congress in 2011.11 From a majority of 156 seats out of 294 in undivided Andhra Pradesh in 2009, the Congress was reduced to 21 seats in the 2014 Andhra Pradesh assembly elections (Figure 5). Though YSR Congress, with 70 seats, was unable to form the government, it served as the principal opposition member to the Telugu Desam government.

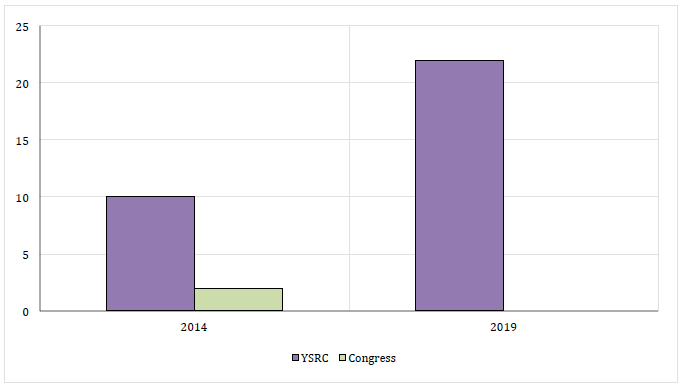

By 2019, YSR Congress had more than doubled its seat share, securing a comfortable majority of 151 seats out of 175 and Jagan was appointed chief minister. A similar trend was visible in the Lok Sabha performance of the Congress and YSR Congress: from 33 seats in undivided Andhra Pradesh in 2009, The Congress’ seat share in bifurcated Andhra Pradesh plunged to two in 2014, and zero in 2019 (figure 6). Meanwhile, YSR Congress secured 10 seats in 2014 – when Jagan was elected as an MP – and 22 in 2019.

Figure 5: YSR Congress vs Congress, Andhra Pradesh Assembly Elections

Source: ECI

Figure 6: YSR Congress vs Congress, Andhra Pradesh Lok Sabha

Source: ECI

Individual Defections

Besides the breakaway parties, which have either decimated the Congress or significantly reduced its strength in those states, the more common kind of defections from the Congress in the last few years have been of elected MLAs, defecting alone or in groups, to topple elected state governments.

Madhya Pradesh was the most recent instance: 22 Congress MLAs, led by four-time MP Jyotiraditya Scindia, resigned in March 2020, defecting to the BJP shortly after.12 Chief Minister Kamal Nath’s government, which had 114 out of 230 seats in the Assembly, was consequently forced out. The BJP went on to form the government with three-time chief minister, Shivraj Singh Chouhan, returning to power. Scindia has since been nominated to the Rajya Sabha from Madhya Pradesh.

The developments in Madhya Pradesh come less than a year after the Congress-Janata Dal (Secular) government in Karnataka was similarly toppled in July 2019, when 17 MLAs (13 from the Congress) in the H D Kumaraswamy-led government defected to the BJP, causing the government to lose its majority. Eleven defectors won the by-polls in September 2019 on a BJP ticket.13 Similarly, in Uttarakhand, 14 Congress MLAs defected to the BJP in 2016 and contested the 2017 Assembly elections on BJP tickets, and 12 of them retained their seats.14

In Arunachal Pradesh, Chief Minister Pema Khandu and 42 other MLAs defected from the Congress to the People’s Party of Arunachal Pradesh to form the government in alliance with the BJP in 2016, reducing the Congress from 44 MLAs to just one.15 In the 2019 Assembly elections, BJP, under Khandu, secured a comfortable majority of 41 out of 60 seats.

Conclusion

The Congress is at its lowest point with successive failures in the 2014 and 2019 general elections and marginalisation in several states. As Suhas Palshikar starkly puts it, “If the 10 years from 1989 were years of decline, post 2014, the Congress began to face an existential crisis for the first time.” 16 The problem has been compounded by the steady defections of its leaders.

One of the primary reasons for the spate of defections is the existence of a dominant BJP that is able to attract Congress defectors and offer the perks of government. The weaknesses within the Congress have aided this process. The party has been operating in an “ideological vacuum” and has found it difficult to take a different line from the BJP on a host of contentious issues, including Kashmir and the Ram temple at Ayodhya. Besides, factional feuding “remains institutionalized” 17 within the party, making it prone to defections and formation of splinter parties.

There are no quick solutions to stem defections. James Manor has offered some solutions and suggested that re-federalisation of the party and organisation building held the most promise. He argues that for this to happen state-level Congress leaders must be given freedom and authority. There have been some calls for change, including a letter by 23 Congress leaders in 2020 demanding changes in the party organisation. The party high command has been dismissive of such efforts. If the Congress leadership shows no appetite for rebuilding or reinventing the party, defections will continue unabated.

. . . . .

Dr Ronojoy Sen is Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (Politics, Society and Governance) at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isasrs@nus.edu.sg. Ms Srishti Gupta is a former intern at ISAS. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons/Gage Skidmore

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF