Summary

The Narendra Modi government’s refusal to criticise the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its reluctance to support Western sanctions in Moscow has underlined India’s entrenched Russian connection. Reinforcing the old thinking on Russia is Delhi’s rediscovery of the ‘Global South’ and India’s renewed emphasis on championing the cause of the developing world. However, the apparent continuities in India’s foreign policy since the Jawaharlal Nehru era mask the significant departures in India’s international relations under Modi.

Some of the recent trends in Indian foreign policy highlight the significant elements of continuity in the foreign policies of the National Democratic Alliance government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Nehruvian principles of India’s engagement with the world. Some scholars of Indian foreign policy have argued that India’s foreign policy since 1991 has changed dramatically and that the Modi era marks a definitive break from the Nehruvian policies.[1] Others have argued that the change is overestimated and there is essential continuity in the way India deals with the world.[2] While both continuity and change are not mutually exclusive in the foreign policies of most nations, this paper argues that there have been major structural changes in the Indian engagement with the world and that these trends have accelerated under Modi.

Two elements of continuity stand out. One is India’s relationship with Russia, and the other is the renewed ambition under the Modi government to lead the so-called ‘Global South’ that comprises the developing world in Asia, Africa and Latin America. While Russia remains an important partner, especially in the defence sector, I argue here that the salience of Moscow in India’s great power relations is in decline. Although India has rediscovered the ‘Global South’ under the Modi government, it is not a return to the past. In fact, it is just one feature of its growing engagement with a range of regional and global institutions. The emphasis on the ‘Global South’ does not take away the growing weight of the major powers, especially the United States (US), and its allies in Europe and Asia, in India’s international relations.

Complementing the continuities are three major changes in India’s international relations. The first is the shift from emphasising Asian solidarity to constructing a new balance of power system in the Indo-Pacific; the second is the growing security partnerships with the West that complement traditional centrality of Russia in Delhi’s strategic calculus; and the third is the shift from the pursuit of Third World leadership to the engagement with a range of diverse institutions, including those dominated by the major powers. These three changes are likely to prove more consequential over the long term than the continuities in Indian foreign policy.

Let us now examine the three trends in greater detail.

The idea of Asian solidarity had a powerful appeal to the Indian national movement in the interwar period and had an enormous influence on India’s international affairs in the twentieth century.[3] As India began to acquire a modern national consciousness, it began to discover shared heritage with other Asian cultures. That these civilisations were older than those of the European colonial powers enhanced the nationalist sense of self-worth. This, in turn, got an enormous boost from the growing contacts between various Asian nationalist movements fighting to end European colonialism.

The solidarity, however, could not be consolidated into joint action in the Second World War. The Indian and Chinese nationalist movements, for example, fought different imperial powers – Britain and Japan respectively – and could not coordinate their strategies. Yet, the idea of forging post-war unity among the Asian countries was at the top of India’s agenda. It was reflected in the first foreign policy initiative that Jawaharlal Nehru took – the Asian Relations Conference – months before India gained its formal independence in August 1947. This was followed by the Afro-Asian Conference at Bandung in 1955. The euphoric attempt at building non-Western regional order came crashing down in 1962 when China attacked India in 1962.[4]

As Nehru’s world shattered, he turned to John F Kennedy, the US president, for help in dealing with the Chinese aggression. While it looked like a new chapter would unfold between India and the US, Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 saw the breakdown of the brief bonhomie and Delhi turned to Moscow to meet the Chinese challenge.[5] The new conflict between Russia and China helped Moscow and Delhi to build on the converging interests. America’s own rapprochement with China at the turn of the 1970s and their partnership against the Soviet Union deepened the partnership between Delhi and Moscow. By the late 1960s, the idea of Asian unity certainly gave way to a more practical approach to balancing China. However, Delhi would not consciously articulate the doctrine of a balance of power but continued to criticise it. The Sino-US entente and US President Richard Nixon’s tilt towards Pakistan in the 1971 war reinforced anti-Westernism in India.

The end of the Cold War certainly seemed to open the possibilities for a new foreign policy in which anti-Westernism would begin to ebb. However, the US activism on resolving the Kashmir dispute between Delhi and Islamabad and its demand of India rolling back its nuclear weapon programme put Delhi at odds with Washington in the 1990s. The fear that the US unipolar moment might undermine India’s critical national security interests saw Delhi join Moscow and Beijing to develop a coalition – the Russia-India-China forum – to limit the dangers of the unipolar moment.[6]

However, within two decades, the potential challenge from the US ebbed with the US’ decision not to dabble in Kashmir and Washington’s help in resolving India’s confrontation with the global nuclear order. But as the challenge from China mounted in the second decade of the 21st century – in 2013, 2014, 2017 and 2020 – India moved decisively from the obsession with partnering with China in promoting non-Western solidarity to boosting security ties to the US to balance China. And as the challenge from China continued to mount, India began to formally articulate the pursuit of balance of power in Asia.

Launching the India Centre of the Asia Society Policy Institute in mid-2022, India’s Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar pointed to a “rising but divided Asia”.[7] Underlining the difficulties with the concept of “Asia for Asians”, often promoted by the Chinese today, Jaishankar said, this “…presumes a stronger convergence within the continent than reality indicates”. He added that “Asia for Asians is also a sentiment that was encouraged in the past, even in our own country, by political romanticism. The Bandung spirit, however, got its reality check within its first decade. Indeed, the experience of the past affirms that Asians are second to none when it comes to realpolitik”.[8] If keeping the US out of Asia was a preoccupation for Nehru, the Modi government recognises the importance of the US in shaping the regional balance. As Jaishankar put it, “narrow Asian chauvinism is actually against the continent’s own interest…There are resident powers in Asia like the United States or the proximate ones like Australia who have legitimate interests”.[9] America, the distant power, is no longer seen as a threat to India, but it is the neighbouring China that is viewed as undermining India’s core national security interests.

The second was the decisive transition from Russia-centred defence policies towards a growing weight of the security ties with the US and its allies. The core principle of non-alignment was to reject military alliances of the superpowers of the Cold War – the US and the Soviet Union. However, in practice, India had to bend that principle as it coped with security challenges that confronted it. As noted above, the idea that India could stay away from alliances came under stress in 1962 when Nehru turned to Kennedy for military cooperation. As the crisis in East Pakistan gathered momentum in 1971 and the Sino-US rapprochement began to unfold, Delhi moved to sign a security treaty with the Soviet Union in 1971.

Although it was an alliance for all practical purposes, the Indian discourse continued to define the nation’s foreign policy in terms of non-alignment. The omnibus political coalition that defeated Indira Gandhi in the 1977 elections had accused the prime minister of deviating from the path of non-alignment by getting too close to the Soviet Union. They promised to follow a policy of “genuine non-alignment”. However, once they got into power, the strategic partnership with Russia did little to change the engagement with Russia.[10] The bipartisan consensus on close ties with Russia not only outlasted the Soviet Union but has remained significant after a few bumps in the 1990s.

The Modi government continued to invest in the Russian relationship, but the salience of Moscow has begun to steadily erode in the 21st century. For one, rapid economic growth since the 1990s saw India become a larger economy than Russia – in 2022, India’s gross domestic product at US$3.5 trillion (S$4.7 trillion) was nearly double Russia’s at $1.7 trillion (S$2.3 trillion). As the Russian economy shrinks amidst the massive Western sanctions imposed the economic gap between the two sides will continue to grow. On the trade front, Russia has become steadily marginal. In the 1990s, the Soviet Union was India’s top trading partner with two-way commerce at about US$5.5 billion (S$7.5 billion). The US followed close behind with US$5.1 billion (S$6.9 billion).[11] Three decades later, India’s trade with Russia was anaemic at less than US$10 billion (S$13.6 billion) during 2020-21.[12] There was a surge in bilateral trade in 2022 as India began to import large quantities of discounted Russian oil amidst the tightening global oil market after the Russian aggression against Ukraine.[13] India’s trade with the US in 2021 was at nearly $160 billion (S$217 billion), including goods and services.[14]

What has endured though is India’s continued dependence on Russian weapons. Although India has diversified its weapons imports in the 21st century by acquiring more arms from the US, France and Israel, Russia still accounts for more than 70 per cent of India’s total inventory. Delhi’s dependence on Moscow for spares and other equipment remains deep and has acquired a sharp edge amidst India’s conflict with China on its long and contested border. It is this dependence that has, among other reasons, compelled India to maintain silence over the Russian aggression in Europe.

While Russia remains an important defence partner for India, the story of the last 20 years has been the growing security cooperation with the US and its allies in Europe and Asia. This includes a growing number of military exchanges, bilateral and minilateral joint exercises, the purchase of advanced weapons, and strategic coalitions like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Australia, India, Japan and the US) [the Quad]. Although India continues to sit in the Russia-India-China grouping and BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), it is the Quad that sees the new innovations in India’s security policy. India’s past reliance on Russia to balance China has become less sustainable amidst the growing strategic partnership between Moscow and Beijing.[15]

The third is the shift from India’s pursuit of Third World leadership that peaked in the Cold War to building like-minded coalitions in the Modi era. As the idea of Asian solidarity took a back seat after 1962, India’s enthusiasm for building a global non-aligned movement gained much ground in the 1960s and acquired considerable traction in the 1970s as the Indian foreign policy acquired a radical tone. After the Cold War, India’s focus moved away from the non-aligned movement to the emphasis on regional cooperation in the immediate and extended neighbourhoods, increased economic cooperation with the major economies and reworking its great power relations. India’s focus also shifted to groupings with major powers like the BRICS, the Quad and the G-4 (Brazil, Germany, India and Japan seeking United Nations Security Council reform). India also devoted much energy to engaging multilateral institutions like the G-20 and the G-7, and regional institutions like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Under Modi, we have seen India renew its interest in engaging the non-aligned movement and more broadly the ‘Global South’. This engagement, however, is not in the old template of mobilising the South against the West. Jaishankar has articulated the idea of India as a “south western power” – one that acts as a bridge between the West and the South. The emphasis on the ‘Global South’ can also be viewed as part of India’s competition with China for regional and global influence. Having built considerable equities in the developing world during the Cold War, Delhi does not want to simply abandon them.[16] It is also being suggested in Delhi that the US prefers the Indian leadership of the South rather than letting Beijing and Moscow dominate this important part of the world.[17] These element changes in Indian foreign policy point to a sophisticated diplomacy that matches India’s growing material power in the Modi era. Some of the older connections endure but in a very different context.

. . . . .

Professor C Raja Mohan is a Visiting Research Professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute in the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at crmohan@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

[1] See for example, C Raja Mohan, Crossing the Rubicon: The shaping of a New Indian Foreign Policy (New York: Palgrave, 2004) and Modi’s World: Expanding India’s Sphere of Influence (Delhi: Harper Collins, 2015).

[2] Rajesh Basrur, “Modi’s foreign policy fundamentals: A trajectory unchanged”, International Affairs, Vol. 93, no. 1, January 2017.

[3] Christophe Jaffrelot, “India’s Look East Policy: An Asianist Strategy in Perspective”, India Review, Vol. 2, No. 2, June 2003.

[4] Andrea Benvenuti, “Nehru’s Bandung Moment: India and the Convening of the 1955 Asian-African Conference”, India Review, Vol. 21, No. 2, June 2022.

[5] Bruce Riedel, JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, the CIA, and the Sino-Indian War (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2017).

[6] Frank O’Donnell and Michaela Papa, “India’s multi-alignment management and the Russia-India- China triangle”, International Affairs, Vol. 97, No. 3, May 2021.

[7] Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, “Remarks at the launch of Asia Society Policy Institute”, New Delhi, 29 August 2022, https://mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/35662/Remarks_by_External_Affairs_Minister_ Dr_S_Jaishankar_at_the_launch_of_Asia_Society_Policy_Institute.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] R V R Chadrasekhara Rao, “The Janata Government and the Soviet Connexion”, World Today, Vol. 34, No. 2, February 1978.

[11] Details available at https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/IND/Year/1990/Summarytext.

[12] See Embassy of India, “Brief of India-Russia Economic Relations”, 2021, https://www.indianembassy-moscow.gov.in/overview.php.

[13] It remains to be seen if this trend lasts; see “Russia is India’s Seventh Largest Trading Partner”, Times of India, 26 October 2022; available at https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/chart-russia-is-now-indias-seventh-largest-trading-partner/articleshow/95090715.cms.

[14] https://www.trade.gov/knowledge-product/exporting-india-market-overview#:~:text=Nonetheless%2C%20bilateral%20U.S.%2DIndia%20trade,the%20United%20States%20and%20India.

[15] C Raja Mohan, “Between the BRICS and the Quad: India’s New Internationalism”, ISAS Brief (Singapore: Institute of South Asian Studies, 6 July 2022, https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/between-the-brics-and-the-quad-indias-new-internationalism/.

[16] C Raja Mohan, “India Rethinks the Non-Aligned Movement”, ISAS Brief (Singapore: Institute of South Asian Studies, 11 May 2020, at https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/india-rethinks-the-non-aligned-movement/. See also, C Raja Mohan, “India’s G-20 Presidency: Championing the Global South”, Indian Express, 6 December 2022, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/india-g20-presidency-c-raja-mohan-opinion-8307870/.

[17] Author’s conversations with senior officials in Delhi, November 2022.

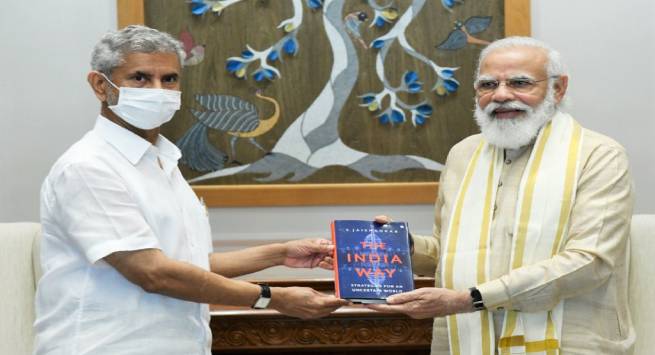

Pic Credit: Jaishankar’s Twitter

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF