Sri Lanka’s Equidistant Policy: Implications for China

Chulanee Attanayake and Archana Atmakuri

12 March 2020Summary

Soon after his election as Sri Lanka’s President, Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s statement about an equidistant foreign policy, and Sri Lanka remaining neutral in the conflict amongst nations, received international attention. The objective of neutrality is ideal for the island nation, especially given the geopolitical interests several major countries seek to pursue through Sri Lanka. However, this policy’s practicality, especially concerning China, has been questioned, as Beijing had enjoyed a special relationship with Colombo during the Mahinda Rajapaksa government. Against this backdrop, this paper examines what an equidistant foreign policy means for Sri Lanka-China relations.

Background

Sri Lanka and China’s relations date back to the times of the Silk Road. Given the geostrategic positioning of the island state, its ports have been frequent stopovers for vessels travelling East and West. Even after China became a People’s Republic, the two countries shared a warm relationship. However, until the early 2000s, China was far from being one of Sri Lanka’s top trading partners, much less a development partner. Beijing’s gradual increase of exports to Sri Lanka thereafter led to it becoming the island’s top trading partner and, later on, its biggest partner in development.

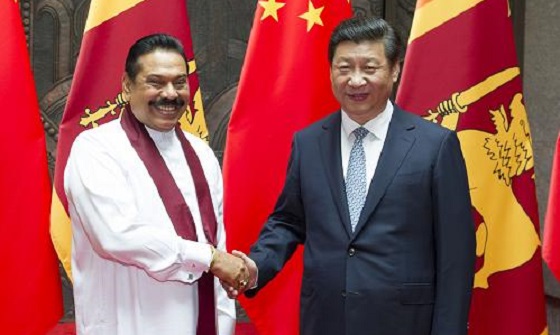

A clear increase in China’s engagement with Sri Lanka took place under the government of Mahinda Rajapaksa, brother of the current President Gotabaya. There was a spike in China’s development aid to Sri Lanka and its exports to Colombo also grew, making Sri Lanka China’s largest export market. This must also be analysed in the context of the mutual interests that have developed over time between Sri Lanka and China.

For Beijing, Sri Lanka’s geographical location in the Indian Ocean offers it a hassle-free route for the movement of goods and trade. This explains why China has committed massive loans for large infrastructure projects – such as the Hambantota Port, Mattala Airport, Norochcholai power plant and Colombo Port City – and why international analysts associate Sri Lanka with China’s so-called ‘String of Pearls’ strategy.1 Now that the Hambantota Port is operated by China’s largest shipping company, China Merchants Port Holdings Company Limited (CMPort), under a 99-year agreement, a new narrative about Sri Lanka falling victim to China’s debt trap diplomacy has gained in prominence.

For an island nation like Sri Lanka, the inflow of investments for infrastructure development is critical. Such projects, in addition to the strong convergence of interests between Mahinda and Chinese leader Hu Jintao, cemented Sri Lanka-China relations. Towards the latter stages of the fight against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in 2008, Sri Lanka received arms support from China, which is said to have helped Colombo win the war. Sri Lanka also received diplomatic support from China at the United Nations throughout this period in response to western allegations of human rights violations during the culmination of the war.

Since then, both countries have expressed mutual interest in strengthening bilateral relations. Given the obvious bonhomie between Sri Lanka and China, it is, therefore, natural to question Gotabaya’s pronouncements of an equidistant foreign policy which proposes to keep a safe distance from major power struggles and engage equally with all countries.

Gotabaya’s Equidistant Foreign Policy

Gotabaya’s equidistant foreign policy would mean Sri Lanka will work with all countries without adversely impacting its relationship with any. This idea, first articulated in his election manifesto, was later reiterated during his swearing-in ceremony and during his visit to India, where he expressed his intention to distance Sri Lanka from major power struggles brewing in the Indian Ocean region and to instead engage the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation and the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation.

Acknowledging India’s sensitivities to Sri Lanka’s foreign policy decisions, in his first interview with Indian media, Gotabaya reinforced Sri Lanka’s stand on not wanting to engage in activities that would threaten India’s national security. The fact that he made his first official visit to India – not China – was also analysed in terms of his commitment to this equidistant policy. He reiterated that Sri Lanka will reach out to other countries besides China for funds and Colombo wants to create an investor-friendly environment. Currently, Chinese investments are huge compared to other powers. To what extent this will be feasible, however, remains a question.

Given Sri Lanka’s strategic geographical positioning and the rising importance of the Indian Ocean in geopolitics, Sri Lanka has become a centre of interest to many global powers. Countries like India, China, the United States (US) and Japan are seen to be using different strategies to woo Sri Lanka and bring it into their respective sphere of influence. As a result, there is strong concern that the island will become the military base of one country or another.

When China’s island presence increased, and later when the Hambantota Port was leased to CMPort, the international community raised concerns about the port becoming a Chinese military base, despite the fact that the port was to be jointly operated by the Sri Lanka Port Authority. While evidence calling the Hambantota Port a Chinese military base is unsubstantiated, the strategic importance of these investments cannot be dismissed.

The narrative of the Hambantota Port becoming a military base and Sri Lanka falling into a debt-trap to China arises from the 99-year lease agreement signed by the Maithripala Sirisena-Ranil Wickremesinghe government in 2017. However, in a substantive study conducted on this debt-trap, China’s non-concessional loans comprise only 20 per cent of Sri Lanka’s total debt from such borrowings. The majority of Sri Lanka’s debt, rather, is due to its failure to meet its obligations to international investors and commercial lenders from a growing and costly practice of foreign borrowing.

Similar domestic concerns were raised in August 2019 when changes were proposed to the Status of Forces Agreement between Sri Lanka and the US signed in 1995. The proposed changes were to grant US military personnel a more streamlined entry into Sri Lanka and to provide diplomatic immunity for such personnel as well as allow them to wear American military uniforms while on the island. Even though this did not raise significant discussion internationally, Sri Lankans viewed this as a blatant infringement of their sovereignty and strongly opposed it.

One important factor to note is that there are multiple players in Sri Lanka who support infrastructure development. Though the amount of independent funds and loans coming from other countries is smaller than that from China, Japan and India, for instance, have been actively pumping funds into the east coast terminal of the Colombo port.

An equidistant foreign policy, therefore, could be a significant opportunity for Sri Lanka to move away from the mainstream narrative of Chinese debt trap diplomacy and avoid getting involved in a power struggle in the Indian Ocean.

Impact on China-Sri Lanka Relations

In the midst of a loud and clear foreign policy agenda promoting non-alignment, what the future holds for Sri Lanka’s long-standing friend, China, is less certain. In an attempt to translate words into action, one significant step Gotabaya took when he came to power was to gazette the Colombo port city as belonging solely to Sri Lanka. China sees the port city project as an integral part of its flagship connectivity plan, the Belt and Road Initiative.

Since the start of this project, it was viewed as an example of Chinese neo-colonialism. Dismissing the prospect of Colombo port city being under China’s control as disinformation, Gotabaya’s announcement reassured foreign investors that Colombo port city was open for business. Similarly, Gotabaya’s statement that the Hambantota Port project agreement would be reviewed garnered attention, and was interpreted to mean that China-Sri Lanka relations could face a rocky road.

However, China-Sri Lanka’s relations, especially under Gotabaya, are too strong to be shaken by such misgivings. Rajapaksa has not forgotten Chinese support for Colombo during the civil war and its aftermath. When Sri Lanka was under pressure from the US and its allies for allegedly violating human rights, China’s support helped to shore up Sri Lanka’s credibility on the international stage. When Sri Lanka was unofficially alienated by its former development partners, China again stepped forward to provide much needed development aid. It was the Rajapaksa government’s successful wartime victory, and the development which afterward ensued, that built Mahinda’s reputation as a doer. In such circumstances, it is unlikely Gotabaya would jeopardise the trust his brother Mahinda built with China.

Even though Gotabaya made his first visit to India and showed sensitivity toward New Delhi regarding Sri Lanka’s foreign policy priorities, neither of these necessarily means its equation with China has changed. It could mean that Gotabaya is attempting to make a genuine effort to build on the progress in the relationship between India and Sri Lanka under the Maithripala Sirisena-Ranil Wickremesinghe government. Hence, the visit could be his way of making New Delhi feel assured of its important place in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy while also not rocking the boat with China.

If Gotabaya continues to stick to a ‘neutral’ foreign policy, Sri Lanka will reap benefits from its relationship with various other powers. His foreign policy, in a way, is a restatement of the non-alignment foreign policies of past Sri Lankan governments. Every Sri Lankan government, upon coming to power, has promised to work with other countries; yet, circumstances have dictated greater cooperation with some countries more than others. It is this circumstantial need that Gotabaya pointed to when explaining that though Sri Lanka is ready to work with everyone, other countries must also look to engage Sri Lanka and not just request Sri Lanka to disengage from China.

Economically, Chinese investments in Sri Lanka are deep-rooted. Since 2005, China has emerged as Sri Lanka’s largest bilateral donor, replacing Japan. As of December 2018, the total foreign financing to be committed by China was US$1,870 million (S$2,599 million).6 Sri Lanka’s debt towards China stood at 12 per cent of the total accumulated debt stock in the country.7 Through such infrastructure funding, China has managed to enhance its foothold in the country, raising concerns by India and other Indian Ocean players about Beijing’s strong presence in the region.

Strategically, Sri Lanka has been and continues to be an important player in the Indian Ocean, given its geography. With the Indo-Pacific receiving greater attention, Sri Lanka might be forced to balance between the two Asian powers – China and India.

Conclusion

An equidistant foreign policy would be necessary for Sri Lanka to maximise its economic opportunities and avoid being entangled in great power politics. However, it is important to note that small states such as Sri Lanka will invariably be dragged into power conflicts, whether they like it or not. Given that the Indo-Pacific is gaining prominence and Sri Lanka sits at the heart of the Indian Ocean, it cannot avoid lending the strategy its support. On the other hand, Sri Lanka is heavily reliant on Chinese infrastructure loans and funds. By and large, since Sri Lanka would have a greater interest in fostering development partnerships, it will definitely prefer China as it is currently the country that is most interested in providing funds.

. . . . .

Dr Chulanee Attanayake is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). She can be contacted at chulanee@nus.edu.sg. Ms Archana Atmakuri is a Research Analyst at the same institute. She can be contacted at isasala@nus.edu.sg. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

-

More From :

More From :

-

Tags :

Tags :

-

Download PDF

Download PDF